| Dayenu: "it's enough for us." So we sing at every Passover seder. But what's enough, anyway? As Passover gathers us to celebrate freedom both ancestral and modern, what "enough" could there possibly be in liberation? And why would such a beloved Jewish tradition offer this curious declaration? Turns out, enough is both far more and far less than we might imagine. |

By Rabbi David Evan Markus

I adore Passover – for what the holiday is, how it gathers people around a shared table for song and celebration, and how it is so totally and utterly itself.

For the next few weeks, this column will shift from the Torah cycle to Passover. (This week's Torah portion is Tazria.) This switch feels fitting and important, because this year's Passover is especially meaningful. It's not that I don't love Torah – I do. It's that I adore Passover.

To explain why, here's a story about stories about stories.

In 1994, I was a college senior on tour with a music group. In a university bookstore, I came onto a new book, The Jew in the Lotus by Rodger Kamenetz, who would become my teacher and friend. A poet of the American Jewish experience, Rodger wrote the true story of a group of rabbis whom His Holiness The XIV Dalai Lama called to his Tibetan government in exile in Dharamsala, India, to ask them their secret.

The Dalai Lama asked the rabbis, "How did the Jews do it?" How did the Jewish people survive and thrive amidst exile and oppression?

Rodger's book, now a classic of Jewish life, told of how rabbis across the breadth of Jewish life shared some of Judaism's secrets with the Dalai Lama, who faced the Tibetan people's own exile and oppression.

One secret the rabbis shared is Passover.

As it happens, the Jews and Buddhists had something profound in common – and until they sat together, they didn't know it.

We know the Passover story – a Pharaoh who enslaved Joseph's descendants, a redemptive promise kept, a baby in a basket, a bush that burned, a shepherd turned prophet who stood up to power, 10 terrible plagues, a sea that split, a people freed to become a living testament to the One who frees. Passover became the anchor of Western liberation theology, the root narrative of every enslaved people who would become free.

As the Dalai Lama reflected back to the rabbis, Passover is far more than living history lesson: it's an inward journey of becoming. As Exodus 13:8 put it, each of us "does" Passover "for what God did for me when I came forth from Egypt." Each of us is called to regard ourselves as if we ourselves were slaves – trapped, whipped, abused and then miraculously freed.

What keeps it alive and thriving, they shared, is this journey of re-living: not mere memory, but becoming. Tradition and nostalgia are powerful and wonderful in their way, and Passover invites so much more.

Dayenu ("It Would Have Been Enough")

I adore Passover – for what the holiday is, how it gathers people around a shared table for song and celebration, and how it is so totally and utterly itself.

For the next few weeks, this column will shift from the Torah cycle to Passover. (This week's Torah portion is Tazria.) This switch feels fitting and important, because this year's Passover is especially meaningful. It's not that I don't love Torah – I do. It's that I adore Passover.

To explain why, here's a story about stories about stories.

In 1994, I was a college senior on tour with a music group. In a university bookstore, I came onto a new book, The Jew in the Lotus by Rodger Kamenetz, who would become my teacher and friend. A poet of the American Jewish experience, Rodger wrote the true story of a group of rabbis whom His Holiness The XIV Dalai Lama called to his Tibetan government in exile in Dharamsala, India, to ask them their secret.

The Dalai Lama asked the rabbis, "How did the Jews do it?" How did the Jewish people survive and thrive amidst exile and oppression?

Rodger's book, now a classic of Jewish life, told of how rabbis across the breadth of Jewish life shared some of Judaism's secrets with the Dalai Lama, who faced the Tibetan people's own exile and oppression.

One secret the rabbis shared is Passover.

As it happens, the Jews and Buddhists had something profound in common – and until they sat together, they didn't know it.

We know the Passover story – a Pharaoh who enslaved Joseph's descendants, a redemptive promise kept, a baby in a basket, a bush that burned, a shepherd turned prophet who stood up to power, 10 terrible plagues, a sea that split, a people freed to become a living testament to the One who frees. Passover became the anchor of Western liberation theology, the root narrative of every enslaved people who would become free.

As the Dalai Lama reflected back to the rabbis, Passover is far more than living history lesson: it's an inward journey of becoming. As Exodus 13:8 put it, each of us "does" Passover "for what God did for me when I came forth from Egypt." Each of us is called to regard ourselves as if we ourselves were slaves – trapped, whipped, abused and then miraculously freed.

What keeps it alive and thriving, they shared, is this journey of re-living: not mere memory, but becoming. Tradition and nostalgia are powerful and wonderful in their way, and Passover invites so much more.

Dayenu ("It Would Have Been Enough")

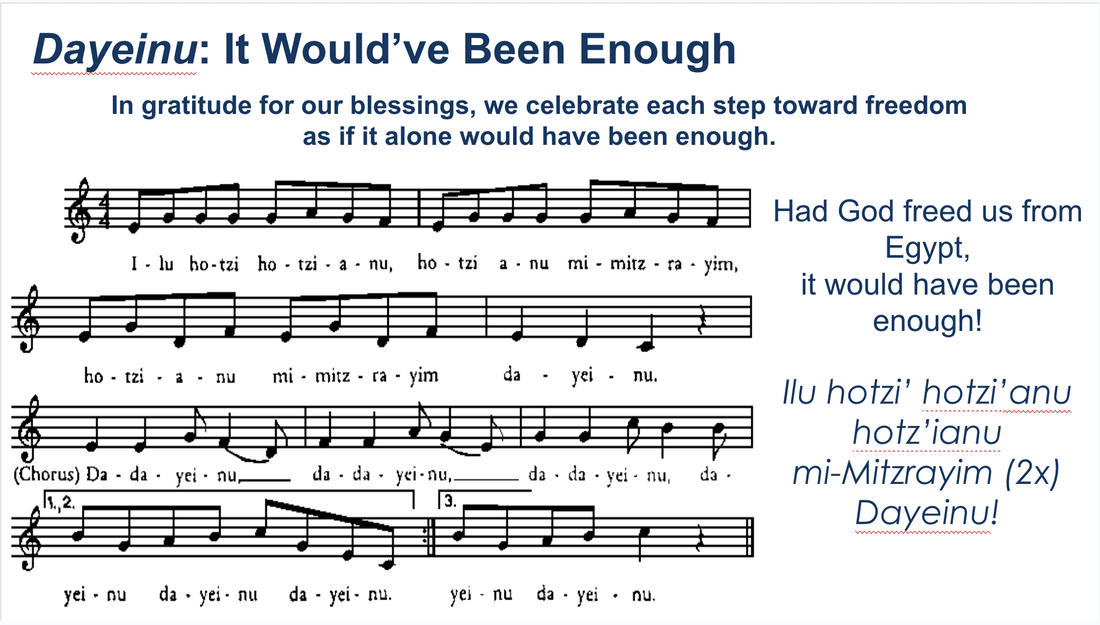

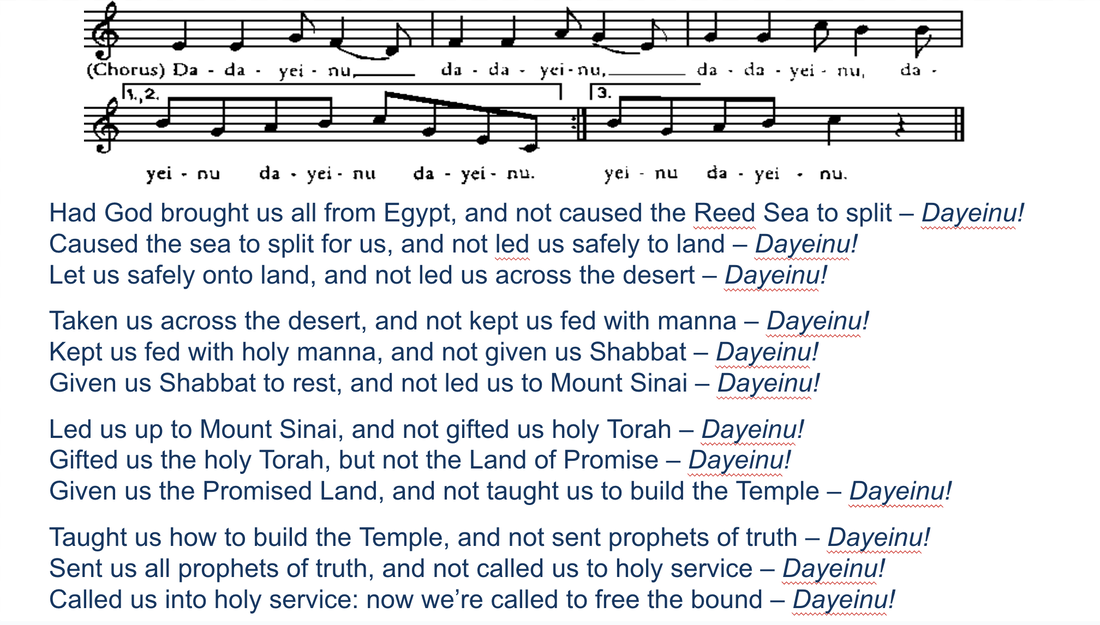

Had God freed us from Egypt, it would have been enough. But think about it: given the rest of the Passover story, Dayenu doesn't seem to make much sense. In the Passover story, had God merely freed us from Egypt and not caused the Sea to split, we wouldn't be here. Or caused the Sea to split but not brought us safely to land? Or brought us safely to land but not led us across the desert?

No food? No Shabbat? No Sinai? No Torah? No Land of Promise? No Temple? No prophets? Nada? If so, then what was the point?

Yet Dayenu is a Jewish classic of Passover. No Passover seder is complete without it. I bet you can hear the tune in your head even now.

Dayenu is fun that contains a deep message, and itself calls us into a journey. Just as Passover calls us to see ourselves as if each of us individually was liberated from Egyptian bondage, Dayenu reminds us to see each step as the whole. Dayenu teaches that this moment is all there is.

Maybe true freedom, true liberation, is living each moment as that whole – each moment as a whole world, each moment being enough.

That was the Dalai Lama's take on Dayenu ("Dalai Dayenu"?). He wasn't suggesting that "now" always is easy. Tibetan exile was and is brutal. The Jewish journey from a ragtag group of freed slaves, through the desert, wars, exiles, oppressions, Holocaust, antisemitism then and now – full of strife and challenge.

Rather, the Dalai Lama, and Dayenu, teach us that calling us into the potential of each moment. Both call us into celebration. Maybe that's the spiritual core of freedom.

Easy to sing, easy to say – harder to do. Especially this year. That'll be the subject of next week's column.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed