| Fresh off liberating miracles and the glory of experiencing the Ten Commandments, our spiritual ancestors freaked out when Moses delayed returning from atop Mount Sinai. To assuage their fears, they had built a Golden Calf and called it the god of their liberation – thereby committing Judaism's original sin. But before we throw stones at such foolishness, let's recall that we too have our Golden Calves that pretend away our anxieties and fears. |

By Rabbi David Evan Markus

Parashat Ki Tisa 5784 (2024)

Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice was correct: "All that glitters is not gold."

Even more, all that glitters is not God – which our desert-wandering spiritual ancestors forgot when they made a Golden Calf to "god" them when Moses delayed in returning from atop Sinai. Fashioning a "god" of gold melted from earrings, they exclaimed (Exodus 32:4), "This is your god, O Israel, who brought you out of the land of Egypt!"

A personal story about glitter and gold: some years ago, I needed to visit a number of state and county legislatures. Fittingly for temples of democracy and public symbols of regional identity and pride, each legislative chamber was beautiful in its own way. In one particularly beautiful legislative chamber, a prominent public official boasted about the especially ornate gold plating on the walls.

At that very moment, multiple leaders of that legislative chamber were facing (and soon would be convicted on) public corruption charges. The ornate gold, and the boasting of it, seemed to conceal as much as it revealed. Even more, it seemed to miss the point: a legislative body's truest gold is a healthy democracy, not wall ornaments.

Ornate places can inspire awe, wonder, piety, spaciousness and reverence. The world's most beautiful temples, churches and mosques are designed for precisely those purposes. They are tourist attractions and also vibrant centers of community, prayer, learning and service.

Parashat Ki Tisa 5784 (2024)

Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice was correct: "All that glitters is not gold."

Even more, all that glitters is not God – which our desert-wandering spiritual ancestors forgot when they made a Golden Calf to "god" them when Moses delayed in returning from atop Sinai. Fashioning a "god" of gold melted from earrings, they exclaimed (Exodus 32:4), "This is your god, O Israel, who brought you out of the land of Egypt!"

A personal story about glitter and gold: some years ago, I needed to visit a number of state and county legislatures. Fittingly for temples of democracy and public symbols of regional identity and pride, each legislative chamber was beautiful in its own way. In one particularly beautiful legislative chamber, a prominent public official boasted about the especially ornate gold plating on the walls.

At that very moment, multiple leaders of that legislative chamber were facing (and soon would be convicted on) public corruption charges. The ornate gold, and the boasting of it, seemed to conceal as much as it revealed. Even more, it seemed to miss the point: a legislative body's truest gold is a healthy democracy, not wall ornaments.

Ornate places can inspire awe, wonder, piety, spaciousness and reverence. The world's most beautiful temples, churches and mosques are designed for precisely those purposes. They are tourist attractions and also vibrant centers of community, prayer, learning and service.

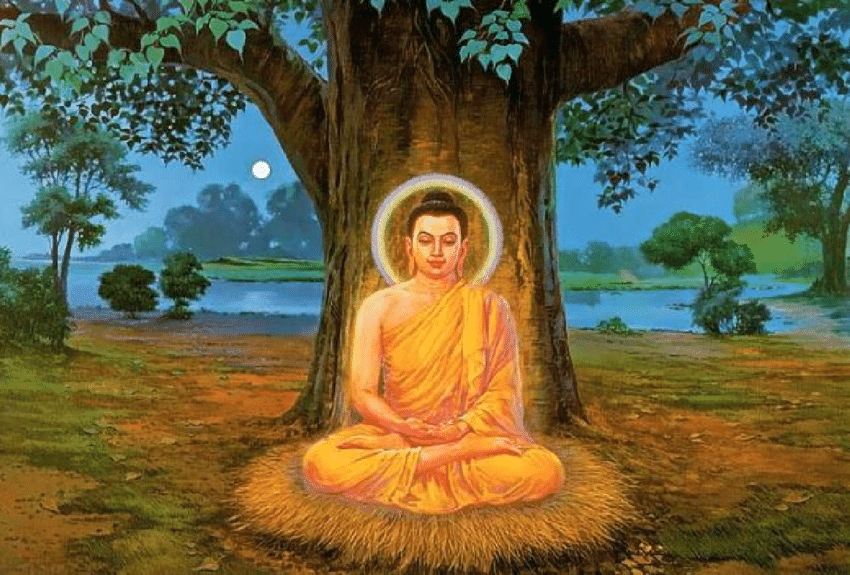

| Nothing against awe-inspiring buildings or the means necessary to build and maintain them, but it's worth remembering that the sacred texts of every major spiritual tradition record the One we call God to manifest just about everywhere except ornate places. To ancient Israelites, God "appeared" as a Voice in the wilderness, an outdoor wrestle, in a burning bush, by daytime cloud and nighttime fire leading former slaves across a desert, a consuming fire atop an altar, in prophetic dreams and visions, and by a "still, small voice" within. Christian and Muslim traditions hold that God similarly manifested in light, visions and prophesies – usually in nature, and almost always in isolated places without worldly distraction. The Buddha attained enlightenment not in a temple but outside under a tree. The settings of Hinduism's sacred Bhagavad Gita and Mahabharata were battlefields (both physical and metaphysical). Native religions are likewise, as is Persian Zoroastrianism. Divinity manifesting as the ornate? the golden? Uh, Not so much. |

Against this backdrop, it's easy for us moderns to rail at the Golden Calf. Of course it violated the First Commandment about God being our liberator. Of course it violated the Second Commandment against making idols for worship. Of course it was motivated by anxiety and fear about Moses not returning from atop Sinai. Of course it bespoke an utter lack of faith despite countless miracles already unfolding. Of course our spiritual ancestors didn't get it.

Of course. Yet how often do we ourselves fall into similar traps of mind and heart? How often do we forget who we truly are, and what Power (call it what you will) makes us truly free from bondage? How often do we build and worship Golden Calves of power, status, rightness, wealth, charisma, popularity or persona? How often does our own fear of inadequacy, loneliness, suffering, discomfort or truth impel all kinds of behaviors to avert the pain of fear? How often do we cover pain, fear, foibles or worse in something glittery?

If we think about it, we know our Golden Calves don't do all that we impute to them. Yet habit, the impulse to avoid unpleasant emotions, and especially the societal prevalence of making idols of things and ideas, are powerful intoxicants. Maybe that's why the Golden Calf episode returns every year: to prod us to face these potent intoxicants in our lives... the ones that lure us into forgetting who we really are.

Granted, ancient Judaism had its glittery golden Mishkan – God's "indwelling place" from the days of desert wandering through to the First and Second Temples. But spiritually speaking, the Mishkan wasn't about the gold. It was about the negative space between the Ark's adorning angels' wings, from which the Voice was heard (Exodus 25:17-22).

Spiritual life often is about the negative space, the Voice and listening deeply. These are the very opposites of the literal Golden Calf of ancient times and the figurative Golden Calves of our modern lives.

Maybe that's why the Golden Calf (theirs, and ours) is Judaism's "original sin." Put another way, all that glitters isn't God.

Of course. Yet how often do we ourselves fall into similar traps of mind and heart? How often do we forget who we truly are, and what Power (call it what you will) makes us truly free from bondage? How often do we build and worship Golden Calves of power, status, rightness, wealth, charisma, popularity or persona? How often does our own fear of inadequacy, loneliness, suffering, discomfort or truth impel all kinds of behaviors to avert the pain of fear? How often do we cover pain, fear, foibles or worse in something glittery?

If we think about it, we know our Golden Calves don't do all that we impute to them. Yet habit, the impulse to avoid unpleasant emotions, and especially the societal prevalence of making idols of things and ideas, are powerful intoxicants. Maybe that's why the Golden Calf episode returns every year: to prod us to face these potent intoxicants in our lives... the ones that lure us into forgetting who we really are.

Granted, ancient Judaism had its glittery golden Mishkan – God's "indwelling place" from the days of desert wandering through to the First and Second Temples. But spiritually speaking, the Mishkan wasn't about the gold. It was about the negative space between the Ark's adorning angels' wings, from which the Voice was heard (Exodus 25:17-22).

Spiritual life often is about the negative space, the Voice and listening deeply. These are the very opposites of the literal Golden Calf of ancient times and the figurative Golden Calves of our modern lives.

Maybe that's why the Golden Calf (theirs, and ours) is Judaism's "original sin." Put another way, all that glitters isn't God.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed