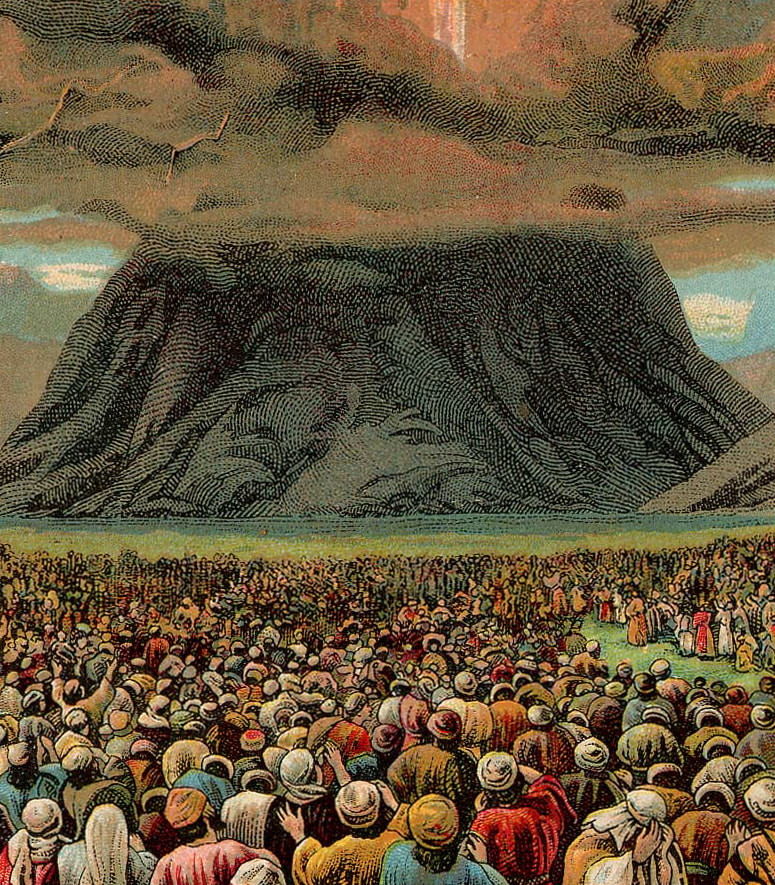

| The journey from meaninglessness to identity to vision to purpose is a journey that hopefully all of us will choose to take throughout our lives. It's the quintessential journey of personal human development. It's also the quintessential journey of collective societal becoming. For our ancient spiritual ancestors freed from Egyptian bondage, seven weeks of desert wandering led them to Sinai. There the Ten Commandments forged with them a new sacred covenant of spirit, ethics, relationship and law – who they were, and what they must become. We've been tripping over it ever sense. |

By Rabbi David Evan Markus

Parashat Yitro 5784 (2024)

"I AM." The first commandment seems anything but one: "I am YHVH your God, who took you out of the Land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery" (Ex. 20:2). Whatever our relationship with commandedness – God as commander, the spirituality of commands, and how "duty" to "comply" is expressed and enforced – the first commandment does not scan as a command. It's more a statement of divine identity.

During and after rabbinical school, I must have learned dozens of explanations. Many of the ones I found most meaningful telescoped into the idea that God manifested to our spiritual ancestors as the power of liberation, and therefore began this fateful moment by reprising that calling card.

It was as if God said, "I AM. I took you out. You stand here free because of Me, so know Me and hear Me. It was for this purpose that I took you out. Your freedom is for this." That's why Moses relayed to the people on God's behalf these fateful words just before the Ten Commandments (Ex. 19:4-6):

Parashat Yitro 5784 (2024)

"I AM." The first commandment seems anything but one: "I am YHVH your God, who took you out of the Land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery" (Ex. 20:2). Whatever our relationship with commandedness – God as commander, the spirituality of commands, and how "duty" to "comply" is expressed and enforced – the first commandment does not scan as a command. It's more a statement of divine identity.

During and after rabbinical school, I must have learned dozens of explanations. Many of the ones I found most meaningful telescoped into the idea that God manifested to our spiritual ancestors as the power of liberation, and therefore began this fateful moment by reprising that calling card.

It was as if God said, "I AM. I took you out. You stand here free because of Me, so know Me and hear Me. It was for this purpose that I took you out. Your freedom is for this." That's why Moses relayed to the people on God's behalf these fateful words just before the Ten Commandments (Ex. 19:4-6):

| אַתֶּ֣ם רְאִיתֶ֔ם אֲשֶׁ֥ר עָשִׂ֖יתִי לְמִצְרָ֑יִם וָאֶשָּׂ֤א אֶתְכֶם֙ עַל־כַּנְפֵ֣י נְשָׁרִ֔ים וָאָבִ֥א אֶתְכֶ֖ם אֵלָֽי׃ וְעַתָּ֗ה אִם־שָׁמ֤וֹעַ תִּשְׁמְעוּ֙ בְּקֹלִ֔י וּשְׁמַרְתֶּ֖ם אֶת־בְּרִיתִ֑י וִהְיִ֨יתֶם לִ֤י סְגֻלָּה֙ מִכָּל־הָ֣עַמִּ֔ים כִּי־לִ֖י כָּל־הָאָֽרֶץ׃ וְאַתֶּ֧ם תִּהְיוּ־לִ֛י מַמְלֶ֥כֶת כֹּהֲנִ֖ים וְג֣וֹי קָד֑וֹשׁ | "You saw what I did to Egypt, how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to Me. Now, if you truly hear My voice and keep My covenant, you will be My treasure among all the peoples. Though all the earth is Mine, you will be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation." |

Notice, by the way, that the word is "treasured," not chosen. The idea of Jews as "the chosen people" hails from a mis-translation of this key passage and for centuries fueled a false sense of Jewish arrogance that ignited antisemitism. If anything, the people of this Covenant are "treasured" but not inherently so. We read, rather, that we must be "holy" if we are to be "treasured" – and that's where the Ten Commandments come in.

But our rabbinic ancestors had a problem. Covenants – holy relationships of mutuality – are supposed to be voluntary. The rabbis saw our ancestors newly liberated, spiritually pediatric, kvetchy, wholly dependent on God for food (manna) and water (Miriam's mystical well). They were not in a position to say no. The rabbis even imagined that Sinai was upturned over their heads, like a huppah (wedding canopy) but still as a mountain, as if God was "marrying" the people while holding a mountain over their heads (B.T. Shabbat 88a). In their vision, God wouldn't take no for an answer.

But voluntarism – our willing, freely given "yes" – was so important that the rabbis also wouldn't take no for an answer. They had to believe that our ancestors somewhere, somehow said yes to the Covenant of their own free will, without a muscular power pressuring assent. And the rabbis found it – of all places, in the Book of Esther, where after defeating Haman the Jews "undertook and irrevocably obligated themselves and their descendants, and all who might join them" (Esther 9:27). Though the Book of Esther plainly meant the celebration of Purim, our Talmudic ancestors re-purposed these words to mean the entire Covenant (B.T. Shabbat 88a).

If so, then the Ten Commandments evoke an altogether different kind of sense – especially the First non-commanding commandment.

My dear friend, Rabbi Mike Moskowitz, who happens to be a fratboy turned frum Orthodox Jew with three Orthodox ordinations, brilliantly reads the First Commandment as God's "coming out," the moment that God tells us who God is. God "comes out" partly to show a calling card (you know Me as your liberator), and also as a model and invitation to us to meet God in our own integrity – in essence to "come out" to God.

My friend Mike meant his teaching partly as an Orthodox validator for the holiness of all human life and therefore also LGBTQ+ life, but Mike's point goes far deeper. In Mike's understanding, and now also in mine, God "comes out" to us so that our whole lives can be a "coming out" to God. It is as if God says, "This is who I am. Now tell me who you are. Better yet: show Me who you are. Show Me how you are in the world –

...in how you relate with Me as an Infinite Unity (Second Commandment),

...in what you say (Third Commandment),

...in how you make Shabbat and sacred time a blessing pump in life (Fourth Commandment),

....in how you treat parents and elders (Fifth Commandment),

...in honoring life by never murdering (Sixth Commandment),

...in honoring sacred partnership by never committing adultery (Seventh Commandment),

...in honoring other people by never stealing (Eighth Commandment),

...in honoring societal justice by never bearing false witness (Ninth Commandment), and

...in honoring neighborly relationship by never coveting (Tenth Commandment).

If we all truly lived this way, we'd truly be "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation." If we truly lived this way, our whole lives would be a perpetual coming out to God. If we truly lived this way, our covenant truly would be a relationship of sacred mutuality, a shining light that can transform the world.

But our rabbinic ancestors had a problem. Covenants – holy relationships of mutuality – are supposed to be voluntary. The rabbis saw our ancestors newly liberated, spiritually pediatric, kvetchy, wholly dependent on God for food (manna) and water (Miriam's mystical well). They were not in a position to say no. The rabbis even imagined that Sinai was upturned over their heads, like a huppah (wedding canopy) but still as a mountain, as if God was "marrying" the people while holding a mountain over their heads (B.T. Shabbat 88a). In their vision, God wouldn't take no for an answer.

But voluntarism – our willing, freely given "yes" – was so important that the rabbis also wouldn't take no for an answer. They had to believe that our ancestors somewhere, somehow said yes to the Covenant of their own free will, without a muscular power pressuring assent. And the rabbis found it – of all places, in the Book of Esther, where after defeating Haman the Jews "undertook and irrevocably obligated themselves and their descendants, and all who might join them" (Esther 9:27). Though the Book of Esther plainly meant the celebration of Purim, our Talmudic ancestors re-purposed these words to mean the entire Covenant (B.T. Shabbat 88a).

If so, then the Ten Commandments evoke an altogether different kind of sense – especially the First non-commanding commandment.

My dear friend, Rabbi Mike Moskowitz, who happens to be a fratboy turned frum Orthodox Jew with three Orthodox ordinations, brilliantly reads the First Commandment as God's "coming out," the moment that God tells us who God is. God "comes out" partly to show a calling card (you know Me as your liberator), and also as a model and invitation to us to meet God in our own integrity – in essence to "come out" to God.

My friend Mike meant his teaching partly as an Orthodox validator for the holiness of all human life and therefore also LGBTQ+ life, but Mike's point goes far deeper. In Mike's understanding, and now also in mine, God "comes out" to us so that our whole lives can be a "coming out" to God. It is as if God says, "This is who I am. Now tell me who you are. Better yet: show Me who you are. Show Me how you are in the world –

...in how you relate with Me as an Infinite Unity (Second Commandment),

...in what you say (Third Commandment),

...in how you make Shabbat and sacred time a blessing pump in life (Fourth Commandment),

....in how you treat parents and elders (Fifth Commandment),

...in honoring life by never murdering (Sixth Commandment),

...in honoring sacred partnership by never committing adultery (Seventh Commandment),

...in honoring other people by never stealing (Eighth Commandment),

...in honoring societal justice by never bearing false witness (Ninth Commandment), and

...in honoring neighborly relationship by never coveting (Tenth Commandment).

If we all truly lived this way, we'd truly be "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation." If we truly lived this way, our whole lives would be a perpetual coming out to God. If we truly lived this way, our covenant truly would be a relationship of sacred mutuality, a shining light that can transform the world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed