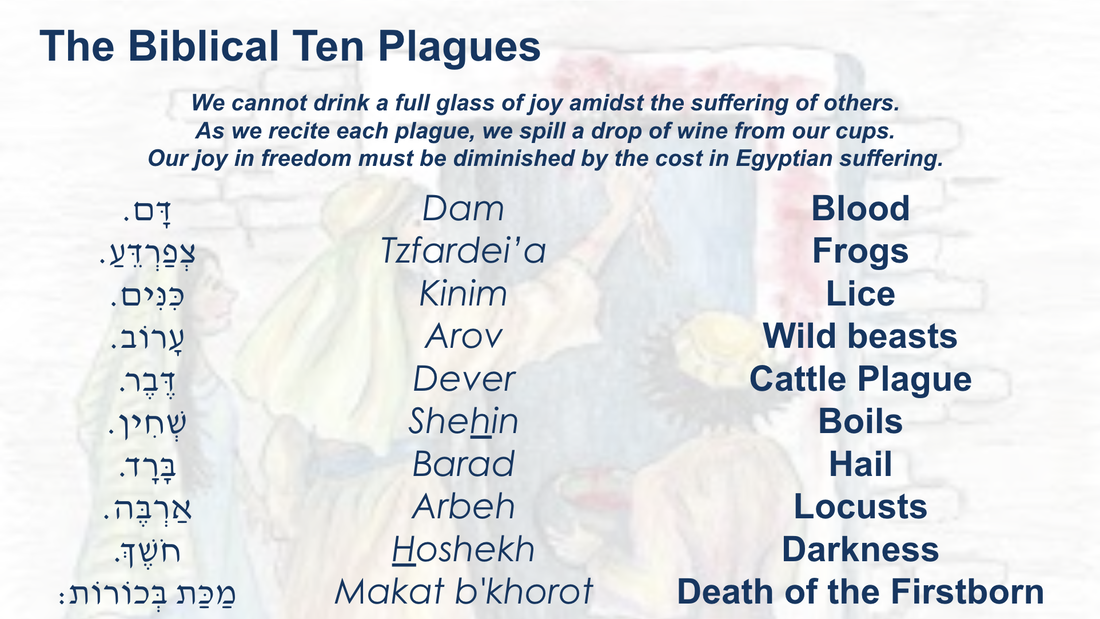

| The freedom we celebrate at Passover is "ours." Each year, we ritually spill a drop from our cups of joy for each of the Ten Plagues, to symbolize that we cannot drink a full cup of joy when our freedom comes at another's high cost. So what can we say this Passover, when the price of freedom, and the cost we risk without it, both are so high? |

By Rabbi David Evan Markus

I've anticipated writing this column since October 7.

Don't ask me how, but I knew on October 7 that Hamas' murder and kidnapping of innocent Israelis – the worst attack on Jews since the Holocaust – would echo all year long. I didn't know exactly what would follow. I certainly didn't know that Israel and a supportive coalition would brush off what otherwise might have been a horrific attack by Iran.

But somehow I knew that, come Passover, I'd need to write this column about freedom and liberation amidst war.

Even as I write these words, with Passover just days away, I pretend no special insight. My clergy colleagues and I hardly know how to finish planning for Passover this year when who knows what geopolitical turns might come next.

I knew I'd grasp for wisdom about what to make of the Haggadah's prescient observation that "in every generation there arise those who seek to destroy us." I'd admit to being tired of fatalism that some "they" seem out to get "us." And I'd equally admit to undeniable truths of too many swastikas, too many white nationalists and exclusions normalized, too many deaf ears turned, too many heads buried in sand.

I knew I'd yearn for a Judaism that embraces radical welcome and belonging in our human and Jewish diversity, without fearing for itself. I'd see the shimmering beauty and inspiration of ancient Passover traditions renewing themselves in our own hands, yearning to share their heart-liberating joy – while also knowing that many of those same hands connect to hearts feeling grief, anxiety, anger, ambivalence or numbness.

What I didn't know on October 7, but should have anticipated, is that the fallout of the Hamas attacks would be literal and gruesome. While the ethics of my Judiciary day job bar me from saying much about the Mideast situation's ultimate causes, I can say that the suffering of innocent Israelis and Gazans singes my soul. Yours, too, I imagine.

And now it's time to write that column.

I've anticipated writing this column since October 7.

Don't ask me how, but I knew on October 7 that Hamas' murder and kidnapping of innocent Israelis – the worst attack on Jews since the Holocaust – would echo all year long. I didn't know exactly what would follow. I certainly didn't know that Israel and a supportive coalition would brush off what otherwise might have been a horrific attack by Iran.

But somehow I knew that, come Passover, I'd need to write this column about freedom and liberation amidst war.

Even as I write these words, with Passover just days away, I pretend no special insight. My clergy colleagues and I hardly know how to finish planning for Passover this year when who knows what geopolitical turns might come next.

I knew I'd grasp for wisdom about what to make of the Haggadah's prescient observation that "in every generation there arise those who seek to destroy us." I'd admit to being tired of fatalism that some "they" seem out to get "us." And I'd equally admit to undeniable truths of too many swastikas, too many white nationalists and exclusions normalized, too many deaf ears turned, too many heads buried in sand.

I knew I'd yearn for a Judaism that embraces radical welcome and belonging in our human and Jewish diversity, without fearing for itself. I'd see the shimmering beauty and inspiration of ancient Passover traditions renewing themselves in our own hands, yearning to share their heart-liberating joy – while also knowing that many of those same hands connect to hearts feeling grief, anxiety, anger, ambivalence or numbness.

What I didn't know on October 7, but should have anticipated, is that the fallout of the Hamas attacks would be literal and gruesome. While the ethics of my Judiciary day job bar me from saying much about the Mideast situation's ultimate causes, I can say that the suffering of innocent Israelis and Gazans singes my soul. Yours, too, I imagine.

And now it's time to write that column.

* * *

On the sacred Passover seder night that we gather to ask why this night is different from all other nights, we also must be clear eyed that this year is like no other year. Even as we unite to celebrate Jewish liberation both ancestral and modern, current events compel us to ask what we mean by "freedom," and for whom, and how we respond to the cost, and who we are – and who we become – in the wake of our answers.

Because make no mistake: no liberation is easy, and no freedom is costless.

Because make no mistake: no liberation is easy, and no freedom is costless.

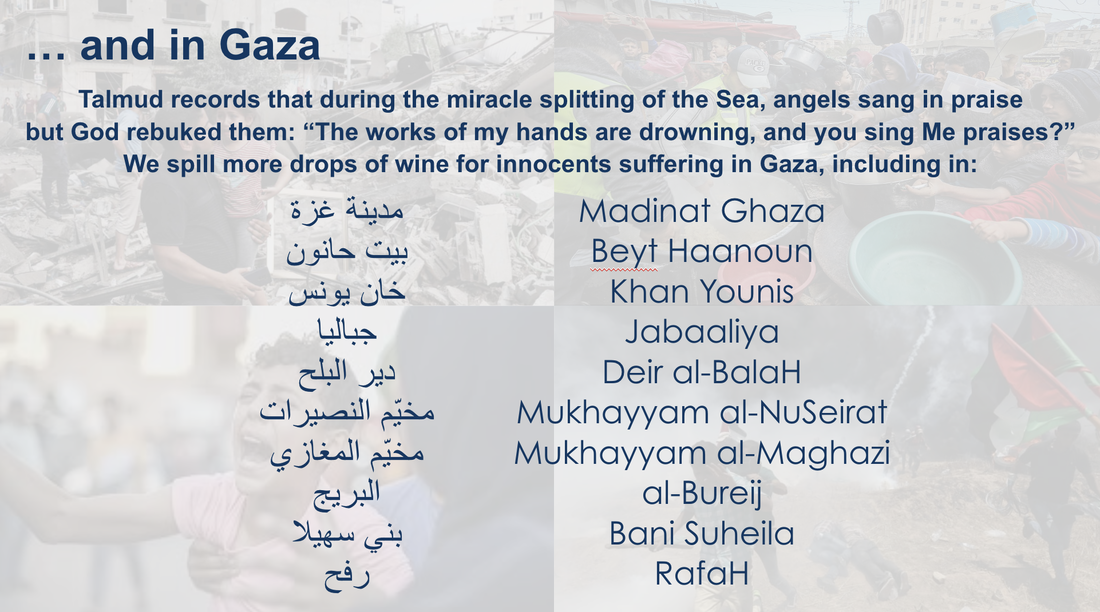

| Talmud's rabbis knew that they needed to teach deep lessons about genuine freedom and true humanity, lest future Jews become haughty or steeled to freedom's cost. They wrote that angels rejoiced as the Egyptian host drowned in the Sea after chasing freed Israelites who miraculously walked through on dry land. But God rebuked the angels: "The works of My hand are drowning, and you sing Me praises?" (B.T. Megillah 10b, B.T. Sanhedrin 39b). |

Each year at Passover, we ritually re-enact this truth that freedom's cost can be tragically high and it's never something to sing about. It's why we spill wine from the second of Passover's four cups – one drop for each of the Ten Plagues. We will not drink a full cup of joy at others' expense.

Spilling wine, of course, is a far cry from spilling blood. We remember how many times the State of Israel has needed to spill blood to preserve itself. Yet again we stand in the shadow of war, when the blood of many thousands is fresh on the ground.

The 1971 Vietnam-era "Crosby, Stills and Nash" sang about the "Cost of Freedom":

Spilling wine, of course, is a far cry from spilling blood. We remember how many times the State of Israel has needed to spill blood to preserve itself. Yet again we stand in the shadow of war, when the blood of many thousands is fresh on the ground.

The 1971 Vietnam-era "Crosby, Stills and Nash" sang about the "Cost of Freedom":

Tragically, so many have laid their bodies down for freedom – too many. The rest of us, Torah commands, are to "live by" mitzvot, not die by them (Lev. 18:5). I hold this mandate to be both literal and figurative. We must live fully – full-minded, full-hearted – amidst all. Put another way, we can't go numb, we can't turn away, and yet we also can't decline to celebrate both ancestral liberty and the hope of freedom renewed in our day.

So what to do? Taking a page from Israel's first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, we will do two seemingly incompatible things, each fully and authentically within its own sphere. We will both celebrate and grieve.

We will celebrate. Celebration of our festivals is a mitzvah. And as Nahman of Breslov put it, "It is a great mitzvah to be in joy."

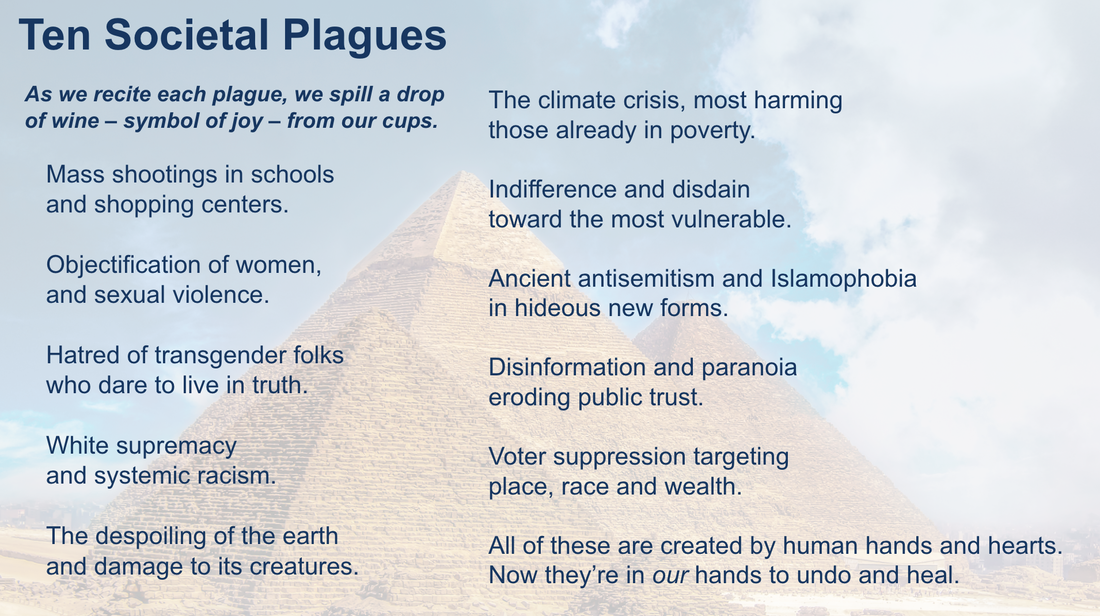

And we will grieve the high cost of freedom. This year the Ten Plagues are not only the Ten Plagues of Biblical history. They're not only 10 societal plagues reverberating through our lives and news feeds. They're also Ten Places in Israel and Ten Places in Gaza. Together we'll spill not 10 drops of wine, but 40:

So what to do? Taking a page from Israel's first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, we will do two seemingly incompatible things, each fully and authentically within its own sphere. We will both celebrate and grieve.

We will celebrate. Celebration of our festivals is a mitzvah. And as Nahman of Breslov put it, "It is a great mitzvah to be in joy."

And we will grieve the high cost of freedom. This year the Ten Plagues are not only the Ten Plagues of Biblical history. They're not only 10 societal plagues reverberating through our lives and news feeds. They're also Ten Places in Israel and Ten Places in Gaza. Together we'll spill not 10 drops of wine, but 40:

What else can we do, and still be us, and still be truly free?

It's not that we claim false equality: we don't. And it's not for us – or at least, not for me – to debate geopolitics at the Passover seder. Among our community, and any community, and probably among many families and seder tables around the world, there are sure to be many views about Mideast geopolitics and governance.

But let there be no debate about the basic humanity and equal dignity that is each person's birthright. If the Jewish people who've known profound suffering cannot mourn the loss of innocent life and especially children whoever they may be, then we have become hardened – maybe no less so than the hardened heart of Pharaoh the slaver. We become no better than the angels whom God rebuked. And we thereby become the opposite of free. If we cannot recognize and deeply feel the tragic deaths of innocents, no matter what our politics, then we are shackled to an inner bondage invisible yet no less stifling than the very bondage we and Passover stand against.

By the same token, if the Jewish people cannot proclaim, protect and celebrate ourselves and our rights among the global family of peoples and nations, if Jews would turn a blind eye to the uniqueness – and unique complexity – of Israel and today's Mideast neighborhood, then we turn our backs on our very selves. That would be a different kind of bondage, but no less profound. Yet this calling comes with special responsibilities: it's not license to withhold just critique even against whom we hold most dear, and it's never permission to stifle or silence innocent others. Those would be yet more kinds of bondage.

True freedom is difficult, but that's what Passover is really about – especially this year. True freedom asks much of us – as individuals, as a people, as a nation. Whatever one's politics, the true cost of freedom is inherently high. And it is worth paying: it is our Covenant to do so, compatibly with the values we claim to hold most dear.

Besides – the heart that cannot grieve the cost of freedom also is the heart that cannot rouse in true joy to fulfill the ancient promise of redemption – though high the cost sometimes may be. If it is on any people, within the capacity of any people, to hold this complexity together, and let it marinate our hearts so that we can stand resiliently against the bondage of every people, then surely it is on us. Especially now.

I pretend no ultimate answers and especially no easy ones. My questions no doubt are yours. No one column or seder or sermon or year can hope to answer them much less to collective satisfaction. But let us begin walking hand in hand through the straits of the narrow place of this moment, and do everything we can to emerge – speedily and in our day – truly and finally free.

It's not that we claim false equality: we don't. And it's not for us – or at least, not for me – to debate geopolitics at the Passover seder. Among our community, and any community, and probably among many families and seder tables around the world, there are sure to be many views about Mideast geopolitics and governance.

But let there be no debate about the basic humanity and equal dignity that is each person's birthright. If the Jewish people who've known profound suffering cannot mourn the loss of innocent life and especially children whoever they may be, then we have become hardened – maybe no less so than the hardened heart of Pharaoh the slaver. We become no better than the angels whom God rebuked. And we thereby become the opposite of free. If we cannot recognize and deeply feel the tragic deaths of innocents, no matter what our politics, then we are shackled to an inner bondage invisible yet no less stifling than the very bondage we and Passover stand against.

By the same token, if the Jewish people cannot proclaim, protect and celebrate ourselves and our rights among the global family of peoples and nations, if Jews would turn a blind eye to the uniqueness – and unique complexity – of Israel and today's Mideast neighborhood, then we turn our backs on our very selves. That would be a different kind of bondage, but no less profound. Yet this calling comes with special responsibilities: it's not license to withhold just critique even against whom we hold most dear, and it's never permission to stifle or silence innocent others. Those would be yet more kinds of bondage.

True freedom is difficult, but that's what Passover is really about – especially this year. True freedom asks much of us – as individuals, as a people, as a nation. Whatever one's politics, the true cost of freedom is inherently high. And it is worth paying: it is our Covenant to do so, compatibly with the values we claim to hold most dear.

Besides – the heart that cannot grieve the cost of freedom also is the heart that cannot rouse in true joy to fulfill the ancient promise of redemption – though high the cost sometimes may be. If it is on any people, within the capacity of any people, to hold this complexity together, and let it marinate our hearts so that we can stand resiliently against the bondage of every people, then surely it is on us. Especially now.

I pretend no ultimate answers and especially no easy ones. My questions no doubt are yours. No one column or seder or sermon or year can hope to answer them much less to collective satisfaction. But let us begin walking hand in hand through the straits of the narrow place of this moment, and do everything we can to emerge – speedily and in our day – truly and finally free.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed