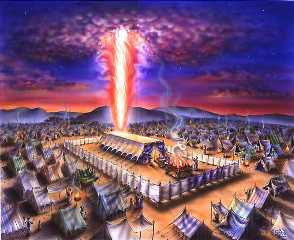

| In the way that most people imagine our spiritual ancestors making their way across the desert to the Land of Promise, Moses followed God... the tribal chiefs followed Moses... and the rest followed the person in front of them. They were like obedient kindergarteners in a school hallway. But as this week's Torah portion relates, everyone saw "the cloud by day and fire by night" at the front of the pack. It was clear to everyone's eyes, for each person to see where they were heading and Who was leading them. And that means everything. |

By Rabbi David Evan Markus

Parashat Pekudei 5784 (2024)

In my continuing first year of mutual introductions and deepening relationships at Shir Ami, and as this week's Torah portion closes the Book of Exodus, I want to share my core concept of what rabbi-ing is and isn't about.

And to do that, as a rabbi, I'd violate my oath of office if I didn't tell a story.

At one time or another, nearly all of my clergy students (and clergy alumni who continue to learn with me) grouse that something feels off-kilter in how they serve. After a while, they'll put their finger on it: they feel like the Professional Jew or Professional Spiritualist, to whom folks outsource vast swaths of Judaism and spirituality. They relate that some congregants seem happy to outsource and follow, while others seem happy to outsource and then kvetch. Either way, they say, something feels off.

I've heard it enough times that I can sing along in harmony. After this recognition, typically next comes anxiety that something is amiss in Judaism. Then comes self-blame: they don't know what they did to foster the dynamic. Then comes the kicker: they must not be cut out for the job.

Me being me, I ask in a hopefully compassionate but slightly evocative way, "What's the job you think you're not cut out for?" Invariably the conversation then turns to what the job is – and, importantly, what it's not.

Parashat Pekudei 5784 (2024)

In my continuing first year of mutual introductions and deepening relationships at Shir Ami, and as this week's Torah portion closes the Book of Exodus, I want to share my core concept of what rabbi-ing is and isn't about.

And to do that, as a rabbi, I'd violate my oath of office if I didn't tell a story.

At one time or another, nearly all of my clergy students (and clergy alumni who continue to learn with me) grouse that something feels off-kilter in how they serve. After a while, they'll put their finger on it: they feel like the Professional Jew or Professional Spiritualist, to whom folks outsource vast swaths of Judaism and spirituality. They relate that some congregants seem happy to outsource and follow, while others seem happy to outsource and then kvetch. Either way, they say, something feels off.

I've heard it enough times that I can sing along in harmony. After this recognition, typically next comes anxiety that something is amiss in Judaism. Then comes self-blame: they don't know what they did to foster the dynamic. Then comes the kicker: they must not be cut out for the job.

Me being me, I ask in a hopefully compassionate but slightly evocative way, "What's the job you think you're not cut out for?" Invariably the conversation then turns to what the job is – and, importantly, what it's not.

* * *

Judaism ain't easy. Judaism's native language (Hebrew), evolution over centuries (many layers), minority status outside Israel, and complex relationship with Israel create real hurdles to heart-and-soul engagement. Jewish education can feel lacking or thin even as ancestral and cultural ties feel strong. The integrity that spiritual life asks can make stubborn and inconvenient demands on heart and mind. Meanwhile, often in Jewish life – and I imagine it's similar in other traditions – folks (knowingly or unknowingly) look to clergy as some dynamic combination of event planner, rite performer, teacher, carer, spokesperson, fount of values, community modulator, community organizer, Official Jew and Official Disappointment.

So the popular impulse to outsource parts of Judaism and spiritual life to clergy is predictable and common. It's what we clergy do with this impulse that matters most.

And that's the job. A rabbi's core job is to redirect this outsourcing impulse and help folks reclaim their own Judaism and spiritual lives for themselves in relationship with tradition and modernity, community and peoplehood. In service of this purpose, clergy listen, write, sing, teach, preach, joke, inspire, cajole, comfort and sometimes afflict. We stick our necks out. We stick our noses in. We make rules, and we break them.

But we mustn't embrace being another's Professional Jew because it's anathema to the core Jewish covenant with each individual person. Judaism doesn't countenance an intermediary between anyone and the One we feebly call God. At the individual level, Judaism is literally one on One. Especially in our liberal spaces that prize both personal autonomy and collective diversity of belief, thought and practice, each person gets to decide how to "Do Jewish" (and even whether to "Do Jewish"). Meanwhile, at the collective level, rabbis are core community members, important ones and maybe elevated when helpful for the role – but not more.

Why tell this story, and why tell it now? Because in this week's Parashat Pekudei, the closing words of the Book of Exodus recount what happened when the Mishkan (traveling focal point for the Indwelling Presence) was activated and the people went on their way (Ex. 40:38):

So the popular impulse to outsource parts of Judaism and spiritual life to clergy is predictable and common. It's what we clergy do with this impulse that matters most.

And that's the job. A rabbi's core job is to redirect this outsourcing impulse and help folks reclaim their own Judaism and spiritual lives for themselves in relationship with tradition and modernity, community and peoplehood. In service of this purpose, clergy listen, write, sing, teach, preach, joke, inspire, cajole, comfort and sometimes afflict. We stick our necks out. We stick our noses in. We make rules, and we break them.

But we mustn't embrace being another's Professional Jew because it's anathema to the core Jewish covenant with each individual person. Judaism doesn't countenance an intermediary between anyone and the One we feebly call God. At the individual level, Judaism is literally one on One. Especially in our liberal spaces that prize both personal autonomy and collective diversity of belief, thought and practice, each person gets to decide how to "Do Jewish" (and even whether to "Do Jewish"). Meanwhile, at the collective level, rabbis are core community members, important ones and maybe elevated when helpful for the role – but not more.

Why tell this story, and why tell it now? Because in this week's Parashat Pekudei, the closing words of the Book of Exodus recount what happened when the Mishkan (traveling focal point for the Indwelling Presence) was activated and the people went on their way (Ex. 40:38):

| כִּי֩ עֲנַ֨ן יהוָ֤׳׳ה עַֽל־הַמִּשְׁכָּן֙ יוֹמָ֔ם וְאֵ֕שׁ תִּהְיֶ֥ה לַ֖יְלָה בּ֑וֹ לְעֵינֵ֥י כָל־בֵּֽית־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל בְּכָל־מַסְעֵיהֶֽם׃ | For a cloud of YHVH was over the Mishkan by day, and fire when night came, in the eyes of all the House of Israel in all their journeys. |

"In the eyes of all the House of Israel" – not just Moses' eyes, not just the rabbi's eyes, not just anyone's eyes, but everyone's eyes.

The question is whether we will see. The truth is that often we don't. The world is hard. The light is hidden, or we turn away from it. Often it can seem easier to follow a person (or not follow a person) than to fix one's inner vision on a light that never truly dims – a light there for all to see, if only we will.

The entire purpose of the Book of Exodus, from its first chapters about bondage that we will re-live at Passover, is to bring us from bondage to physical freedom to peoplehood to this very last sentence: a light visible to each person in all our journeys. This light is the Source of everything. This vision is what true liberation is all about, and what we are called to see and be in the world.

It's there, for all to see.

The question is whether we will see. The truth is that often we don't. The world is hard. The light is hidden, or we turn away from it. Often it can seem easier to follow a person (or not follow a person) than to fix one's inner vision on a light that never truly dims – a light there for all to see, if only we will.

The entire purpose of the Book of Exodus, from its first chapters about bondage that we will re-live at Passover, is to bring us from bondage to physical freedom to peoplehood to this very last sentence: a light visible to each person in all our journeys. This light is the Source of everything. This vision is what true liberation is all about, and what we are called to see and be in the world.

It's there, for all to see.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed