By Rabbi David Evan Markus

Erev Rosh Hashanah 5784 (2023)

Erev Rosh Hashanah 5784 (2023)

R. David joins a national call to smash the stigma about emotional and mental health in the United States.

Hope and renewal are our birthrights. Claim them as yours, with the power they transmit from legacy and from heaven – and let’s talk if your path feels too steep. Claim your birthright and its inspiration to do more than we think we can – nothing too small – to heal ourselves and this world. Our High Holy Day journey starts here.

Hope and renewal are our birthrights. Claim them as yours, with the power they transmit from legacy and from heaven – and let’s talk if your path feels too steep. Claim your birthright and its inspiration to do more than we think we can – nothing too small – to heal ourselves and this world. Our High Holy Day journey starts here.

Shabbat shalom and shanah tovah! If you’re new to Shir Ami, you're in good company. I started as Shir Ami’s rabbi just two months ago after 13 years in another pulpit. I’m so grateful for tonight’s warm welcome as we begin this new year 5784 together.

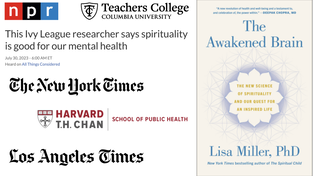

| If you’re an NPR listener like me, maybe you heard Columbia psychologist Lisa Miller describe her research that a vibrant spiritual life is good for us. Peer-reviewed double-blind studies, summarized in her book, The Awakened Brain, showed that a rich spiritual life lowers the risk of addiction by 80%, and suicide by 82%. There have been similarly striking results for depression, pain control and heart health. |

So, mazal tov. Being here is good for you.

I mean, I hope so – but Miller’s focus wasn’t religion much less Judaism. Her focus was spirituality, which is especially notable because Miller is Jewish, and her idea for the study came from Jewish clients at the High Holy Days.

Spirituality and religion aren’t identical, but ideally they rhyme. Religions are spiritual systems encoding values, while spirituality most sustainably flourishes on paths well-walked by cohering communities. But since the 1990s, affiliation rates in all religions are tanking while spirituality booms. The reasons are familiar societal critiques: sagging interest in institutions, leaders who betray trust, erosion of truth, an instant-gratification culture, and digital life in which anyone with a phone can curate a bespoke identity and how the world sees them.

I mean, I hope so – but Miller’s focus wasn’t religion much less Judaism. Her focus was spirituality, which is especially notable because Miller is Jewish, and her idea for the study came from Jewish clients at the High Holy Days.

Spirituality and religion aren’t identical, but ideally they rhyme. Religions are spiritual systems encoding values, while spirituality most sustainably flourishes on paths well-walked by cohering communities. But since the 1990s, affiliation rates in all religions are tanking while spirituality booms. The reasons are familiar societal critiques: sagging interest in institutions, leaders who betray trust, erosion of truth, an instant-gratification culture, and digital life in which anyone with a phone can curate a bespoke identity and how the world sees them.

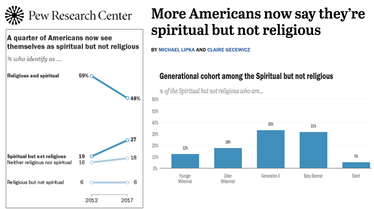

So researchers began studying the Spiritual but Not Religious ("SBNR") – think yoga, SoulCycle, meditation, nature retreats and Burning Man.

In 2017, 25% of U.S. adults called themselves SBNR; now just six years later, it’s up to 30%, including a third of Baby Boomers and Gen-Xers. It’s like spirituality and religion aren’t fully on speaking terms – which is a big deal tonight as Jews gather worldwide, aspiring to renew our lives in the stream of Jewish religion, culture and peoplehood.

In 2017, 25% of U.S. adults called themselves SBNR; now just six years later, it’s up to 30%, including a third of Baby Boomers and Gen-Xers. It’s like spirituality and religion aren’t fully on speaking terms – which is a big deal tonight as Jews gather worldwide, aspiring to renew our lives in the stream of Jewish religion, culture and peoplehood.

Lest anyone imagine that these words were my clever set-up to preach the pitfalls of losing religion, let me disappoint you upfront. It’s not my style, it’s not my role to sell you anything, and it’s not as if vast swaths of society suddenly lost faith in God, a higher power or an ultimate oneness in the world. Spirituality is going strong.

With non-religion spirituality in fashion, what about religion? And what about Judaism, born 3,500 years ago among a desert nomadic tribe, whose sacrificial rituals fell with Jerusalem’s Temple 2,000 years ago, whose Hebrew language is foreign to many of us, whose traditions can feel crusty, a people so often reviled loving a land so often at war?

Are these questions heresy, from a rabbi, who’s new in a pulpit, speaking from the pulpit, on Rosh Hashanah? Not to me, because if Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are truly to help us improve our lives and heal our world, it’ll only be with useful answers to these questions.

Hopefully it’s no surprise that I’m a Judaism fan. The fact that we’re here 3,500 years later, that Judaism isn’t a museum relic, shows Judaism’s resilience and value for human flourishing that has stood the test of time.

In that spirit, my friend Irwin Kula asks an edgy question: “If we’d hire Judaism as an employee, what jobs would we hire Judaism to do – and how well does Judaism do those jobs?” It’s an inverse of the perspective that starts with what Judaism might ask or tell us to do, an important and valuable perspective for sure – but one that's most impactful only if we’re already down with the program.

So let’s ask: if you were hiring Judaism, what would your job description for Judaism be?

During these High Holy Days, we’ll explore a job description for Judaism at this pivotal time in spiritual, national and global life. We’ll vision how a vibrant Judaism authentic to us and this era can thrive, and help us thrive, for our future and the Jewish future depend on it.

To get us started, here’s my list of Judaism’s top goals – the top things we hire Judaism to do for us. I’ll bet sight unseen that anything on your list will connect with mine, which just “happens” to map to our High Holy Day journey:

With non-religion spirituality in fashion, what about religion? And what about Judaism, born 3,500 years ago among a desert nomadic tribe, whose sacrificial rituals fell with Jerusalem’s Temple 2,000 years ago, whose Hebrew language is foreign to many of us, whose traditions can feel crusty, a people so often reviled loving a land so often at war?

Are these questions heresy, from a rabbi, who’s new in a pulpit, speaking from the pulpit, on Rosh Hashanah? Not to me, because if Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are truly to help us improve our lives and heal our world, it’ll only be with useful answers to these questions.

Hopefully it’s no surprise that I’m a Judaism fan. The fact that we’re here 3,500 years later, that Judaism isn’t a museum relic, shows Judaism’s resilience and value for human flourishing that has stood the test of time.

In that spirit, my friend Irwin Kula asks an edgy question: “If we’d hire Judaism as an employee, what jobs would we hire Judaism to do – and how well does Judaism do those jobs?” It’s an inverse of the perspective that starts with what Judaism might ask or tell us to do, an important and valuable perspective for sure – but one that's most impactful only if we’re already down with the program.

So let’s ask: if you were hiring Judaism, what would your job description for Judaism be?

During these High Holy Days, we’ll explore a job description for Judaism at this pivotal time in spiritual, national and global life. We’ll vision how a vibrant Judaism authentic to us and this era can thrive, and help us thrive, for our future and the Jewish future depend on it.

To get us started, here’s my list of Judaism’s top goals – the top things we hire Judaism to do for us. I’ll bet sight unseen that anything on your list will connect with mine, which just “happens” to map to our High Holy Day journey:

We Begin With Hope

We begin with hope and the potential to renew our world. On Erev Rosh Hashanah, Judaism’s ritual birthday of creation, we aspire to harness that energy to reboot ourselves and our world. It’s a nervy claim full of hutzpah – that these days especially can catalyze change, whether inherently or because we make it so. Even more, it claims that we can change, and that we want to change.

Seismic shifts are thrusting change on us – the climate crisis, fascism, attacks on democracy and justice, racism and homophobia, war, resurging antisemitism, fraying civic engagement, all the anger, Israel in turmoil, and so much more. And each of us knows, deep inside, how our own character and behavior have hurt us and others. As Proverbs 14 puts it, each heart knows its own: it marinates in itself.

So changes are urgent – and they’re possible only with hope. As Maimonides wrote 800 years ago, “hope is belief in the plausibility of the possible.” David Hartman went further: “Hope is a category of transcendence, by means of which [one] does not permit what we sense and experience to be the sole criterion of what is possible.” It’s more than optimism. From Jonathan Sacks: “Optimism is a belief that the world is changing for the better; hope is a belief that together we can make the world better. Optimism is a passive virtue; hope is an active one. It needs no courage to be an optimist, but it takes a great deal of courage to hope. The Hebrew Bible is not an optimistic book. It is, however, one of the great literatures of hope.”

True that. Biblical patriarch Abraham left behind everything on the call of an unknown God to go somewhere to be revealed later. Our enslaved ancestors kept traditions alive for centuries, then followed a pillar of cloud and fire for 40 years. Jewish life thrived amidst exile and oppression. The State of Israel, overcoming daunting odds in nearly every field of human endeavor – all impossible without hope.

Jews have been hopemongers for millennia, disbelieving our lying eyes when challenges looked too big or the odds too low. Same for us this Erev Rosh Hashanah for our relationships, our souls, fixing what we helped break, doing our part for our planet and shared civic space. But paradoxically, the enormity of it all can choke hope when we most need it.

So Erev Rosh Hashanah uplifts Judaism’s #1 goal and job description – hope, and with it our capacity to do what’s hard.

Hope is a Jewish superpower, but it’s not magic or DNA. Hope is a learned ability to wrest a potential yes out of the jaws of no, a way of life able to drive the heart where eyes and minds can fear to tread. And Judaism has taught this sacred art for millennia.

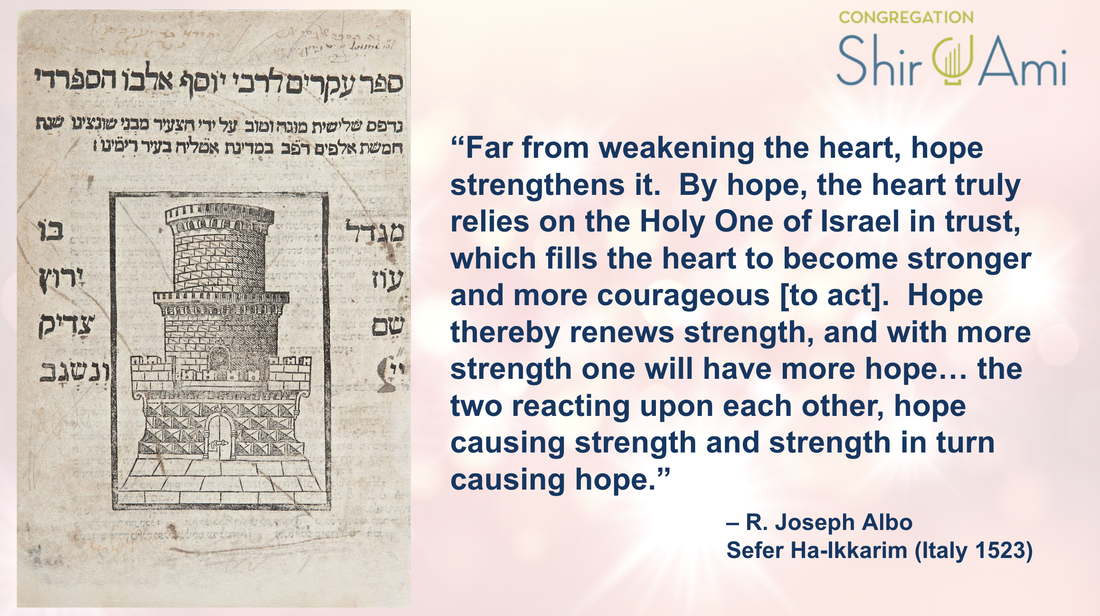

This year is the 500th anniversary of a book from Renaissance Italy, Sefer Ha-Ikkarim by Yosef Albo. To Albo, hope was life’s great tool to build character: life’s every challenge is a new opportunity to cultivate hope. In time, he wrote:

Whether our hope puts God in the center, or spirit, meaning, raw potential or hutzpah – whether we call ourselves religious or spiritual, SBNR or none of the above – hope has been a Jewish superpower.

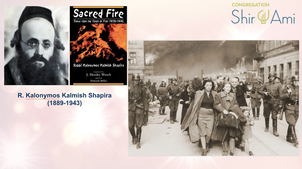

Even during the Holocaust.

The Warsaw Ghetto’s rabbi, Kalmish Shapira, was utterly realistic about his likely fate. But he was fluent in Jewish character development, so he knew in his bones that Judaism encodes hope. In writings he hid in the Ghetto, found in 1960 and published as Aish Kodesh (Sacred Fire), Shapira wrote that to keep hope is to keep alive, and that to lose hope is to lose ourselves and God: we might as well be dead. Shapira’s hope was indomitable: it inspired the Warsaw Ghetto rebellion, bringing hope and courage to millions. Shapira declined a chance to escape lest he leave others, and was murdered in the camps – but he lived, fully and unbowed, to his very last. His words have become timeless.

Today we may not face a ghetto, but there’s a lot on fire: forests, toxic politics, Ukraine, relationships, maybe our own hearts and souls.

No wonder recent years have been such a bear market for hope. There’s been lots of apathy, languishing, malaise and cynicism – and it’s Jewish to admit if hope falters. Hope isn’t a tyrant or taskmaster, as if we fail twice if we feel the weight of the world. The Psalms and Prophets gave voice to all emotions including hopelessness, pleading in dark times, crying out if we feel bereft.

Jewish hope never means pretending away the darkness but rather summoning all our strength – and strength beyond our own – to amplify even the tiniest spark.

And if we see no light, remembering that we once did.

And if we can’t remember, turning to each other and the One we call God so we’re not alone in the dark.

When Hope Fails

But what if that fails? What if darkness grips us so tightly that it’s all we see, all we feel, all we know? It can happen – most often to combat veterans, victims of natural disasters, victims and witnesses of crime, and anyone who experiences serial deaths, one after another.

Dear friends, that now potentially includes all of us alive today, which is why clinical anxiety and depression are raging. From 2020 to 2022, prescriptions for depression and anxiety drugs soared 35% and 65%. In the U.S., 55 million are in counseling, medical treatment or both – and they’re the ones getting help. Millions more still await help because needs far outpace clinical capacity. And many more haven’t sought help at all, quietly thinking that they’re just lazy or weak. Or stoic, not needing help. Or hopeless that help is possible. Or so used to despair that, like proverbial frogs on “slow cook,” they don’t move.

Soon after the 1918 flu pandemic, a second epidemic began. Doctors called it "melancholia" and sent people to health spas. They didn’t yet know that serial losses, or the long-term stress of trying to stay safe, could cause what we now call post-traumatic stress.

Who figured it out? Jewish psychologists. And what nation pioneered sending social workers and counselors as first responders to disaster sites around the world, and funding mental health clinics in neighborhoods hit by terror attacks? Israel.

One of my useless pieces of personal trivia is that I have a bone condition that can cause nerve pain. It’s something I’ve had for a long time, and I’m fine. During the year 2020 it flared up, and my doctor prescribed a new medication. Weeks later, life felt less heavy. Turns out that a different dosage of the same medication helps treats PTSD.

I myself was experiencing clinical PTSD and didn’t know it. 2020 was an unspeakably hard year for so many – but I never had covid. Nobody in my family had covid. Nobody I knew languished on lung bypass. I never lost my job. By comparison I had it easy. But I officiated funerals. I worried. I heard others worry. I lost some of my safety that I took for granted. And I seemed to have no control over any of it.

Over time, these so-called “secondary traumas” affected me – and I wasn’t even aware. I consider myself a capable and well-adjusted person: I serve in government, I'm a pulpit rabbi, I'm an educator and nonprofit leader. I have it together, right? I just figured that I was tired, cranky and oddly distractible for six months. It took friends and a professional to show me that I’d withdrawn, stopped doing things I enjoyed, and lost hope.

And I know my experience was far from unique. To the contrary, it was utterly normal.

My experiences weren’t primary traumas but rather “secondary” ones: I heard, saw and felt a lot of loss, fear and risk. Many of us did. And biologically speaking, the human brain can’t easily distinguish seeing someone hurt from being hurt oneself. Both trigger a cascade of effects – hence today's mental health epidemic in the U.S.

Smashing the Stigma

So today I join my colleagues across the denominations in raising up mental and emotional health care as part of our core covenant as Americans and Jews, as hope when all hope seems lost. It is long past time to smash the stigma that having and naming a mental health challenge makes anyone weak or defective. Rather, it makes us human, and stronger for our ability to name it and address it with wisdom, safety and acceptance.

If the pandemic taught us anything, it’s that mental and emotional health is health. If a broken wrist isn’t cause for shame, then neither is a broken heart, anxiety, depression or a slew of other mental or emotional conditions.

It is our Jewish covenant to seek and spread light – and to seek health and healing. Jews have known trauma, and Judaism encodes hope. Both have been true for centuries. Both are true now.

If you or a loved one is struggling for hope, you’re not alone. There is hope beyond hope. I’m here for you. It’ll take courage. Help often does – and hope always does. It’s okay to be reticent, even afraid to hope, for risk of disappointment. But if our dreams don’t scare us, they’re not big enough. It's worth saying again: if our dreams don't scare us, they're not big enough. Especially now, our world needs our biggest dreams, and our Jewish superpower is equal to them all.

Remember what Rabbi Jonathan Sacks taught: “Hope is a belief that together we can make the world better.” Hope isn’t a castle in the sky: it’s as much an act as an emotion. What’s one more thing you can do to fulfill your hope to improve something hard to change? Choose something: commit, right now, to do that thing. Take that leap of faith. Then think of another one, and do that. Even when we don’t feel hope emotionally, slowly we can “do” our way toward feeling hope anew.

Hope and renewal are our birthrights. Claim them as yours, with the power they transmit from legacy and from heaven – and let’s talk if your path feels too steep. Claim your birthright and its inspiration to do more than we think we can, nothing too small, to heal ourselves and this world. The rest of our High Holy Day journey starts here.

In the end, Judaism is all about hope. It’s one reason why the State of Israel’s national anthem is Hatikvah, literally “the hope.” May we and our loved ones, and our ailing world urgently calling to each of us, be inscribed for a new year of hope and renewal.

Even during the Holocaust.

The Warsaw Ghetto’s rabbi, Kalmish Shapira, was utterly realistic about his likely fate. But he was fluent in Jewish character development, so he knew in his bones that Judaism encodes hope. In writings he hid in the Ghetto, found in 1960 and published as Aish Kodesh (Sacred Fire), Shapira wrote that to keep hope is to keep alive, and that to lose hope is to lose ourselves and God: we might as well be dead. Shapira’s hope was indomitable: it inspired the Warsaw Ghetto rebellion, bringing hope and courage to millions. Shapira declined a chance to escape lest he leave others, and was murdered in the camps – but he lived, fully and unbowed, to his very last. His words have become timeless.

Today we may not face a ghetto, but there’s a lot on fire: forests, toxic politics, Ukraine, relationships, maybe our own hearts and souls.

No wonder recent years have been such a bear market for hope. There’s been lots of apathy, languishing, malaise and cynicism – and it’s Jewish to admit if hope falters. Hope isn’t a tyrant or taskmaster, as if we fail twice if we feel the weight of the world. The Psalms and Prophets gave voice to all emotions including hopelessness, pleading in dark times, crying out if we feel bereft.

Jewish hope never means pretending away the darkness but rather summoning all our strength – and strength beyond our own – to amplify even the tiniest spark.

And if we see no light, remembering that we once did.

And if we can’t remember, turning to each other and the One we call God so we’re not alone in the dark.

When Hope Fails

But what if that fails? What if darkness grips us so tightly that it’s all we see, all we feel, all we know? It can happen – most often to combat veterans, victims of natural disasters, victims and witnesses of crime, and anyone who experiences serial deaths, one after another.

Dear friends, that now potentially includes all of us alive today, which is why clinical anxiety and depression are raging. From 2020 to 2022, prescriptions for depression and anxiety drugs soared 35% and 65%. In the U.S., 55 million are in counseling, medical treatment or both – and they’re the ones getting help. Millions more still await help because needs far outpace clinical capacity. And many more haven’t sought help at all, quietly thinking that they’re just lazy or weak. Or stoic, not needing help. Or hopeless that help is possible. Or so used to despair that, like proverbial frogs on “slow cook,” they don’t move.

Soon after the 1918 flu pandemic, a second epidemic began. Doctors called it "melancholia" and sent people to health spas. They didn’t yet know that serial losses, or the long-term stress of trying to stay safe, could cause what we now call post-traumatic stress.

Who figured it out? Jewish psychologists. And what nation pioneered sending social workers and counselors as first responders to disaster sites around the world, and funding mental health clinics in neighborhoods hit by terror attacks? Israel.

One of my useless pieces of personal trivia is that I have a bone condition that can cause nerve pain. It’s something I’ve had for a long time, and I’m fine. During the year 2020 it flared up, and my doctor prescribed a new medication. Weeks later, life felt less heavy. Turns out that a different dosage of the same medication helps treats PTSD.

I myself was experiencing clinical PTSD and didn’t know it. 2020 was an unspeakably hard year for so many – but I never had covid. Nobody in my family had covid. Nobody I knew languished on lung bypass. I never lost my job. By comparison I had it easy. But I officiated funerals. I worried. I heard others worry. I lost some of my safety that I took for granted. And I seemed to have no control over any of it.

Over time, these so-called “secondary traumas” affected me – and I wasn’t even aware. I consider myself a capable and well-adjusted person: I serve in government, I'm a pulpit rabbi, I'm an educator and nonprofit leader. I have it together, right? I just figured that I was tired, cranky and oddly distractible for six months. It took friends and a professional to show me that I’d withdrawn, stopped doing things I enjoyed, and lost hope.

And I know my experience was far from unique. To the contrary, it was utterly normal.

My experiences weren’t primary traumas but rather “secondary” ones: I heard, saw and felt a lot of loss, fear and risk. Many of us did. And biologically speaking, the human brain can’t easily distinguish seeing someone hurt from being hurt oneself. Both trigger a cascade of effects – hence today's mental health epidemic in the U.S.

Smashing the Stigma

So today I join my colleagues across the denominations in raising up mental and emotional health care as part of our core covenant as Americans and Jews, as hope when all hope seems lost. It is long past time to smash the stigma that having and naming a mental health challenge makes anyone weak or defective. Rather, it makes us human, and stronger for our ability to name it and address it with wisdom, safety and acceptance.

If the pandemic taught us anything, it’s that mental and emotional health is health. If a broken wrist isn’t cause for shame, then neither is a broken heart, anxiety, depression or a slew of other mental or emotional conditions.

It is our Jewish covenant to seek and spread light – and to seek health and healing. Jews have known trauma, and Judaism encodes hope. Both have been true for centuries. Both are true now.

If you or a loved one is struggling for hope, you’re not alone. There is hope beyond hope. I’m here for you. It’ll take courage. Help often does – and hope always does. It’s okay to be reticent, even afraid to hope, for risk of disappointment. But if our dreams don’t scare us, they’re not big enough. It's worth saying again: if our dreams don't scare us, they're not big enough. Especially now, our world needs our biggest dreams, and our Jewish superpower is equal to them all.

Remember what Rabbi Jonathan Sacks taught: “Hope is a belief that together we can make the world better.” Hope isn’t a castle in the sky: it’s as much an act as an emotion. What’s one more thing you can do to fulfill your hope to improve something hard to change? Choose something: commit, right now, to do that thing. Take that leap of faith. Then think of another one, and do that. Even when we don’t feel hope emotionally, slowly we can “do” our way toward feeling hope anew.

Hope and renewal are our birthrights. Claim them as yours, with the power they transmit from legacy and from heaven – and let’s talk if your path feels too steep. Claim your birthright and its inspiration to do more than we think we can, nothing too small, to heal ourselves and this world. The rest of our High Holy Day journey starts here.

In the end, Judaism is all about hope. It’s one reason why the State of Israel’s national anthem is Hatikvah, literally “the hope.” May we and our loved ones, and our ailing world urgently calling to each of us, be inscribed for a new year of hope and renewal.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed