On our trees of life, the spiritual ties that bind, the human penchant for the inner avoidance mechanism called "spiritual bypassing," Yom Kippur as our call to "answer" our souls rather than "afflict" them, taking the inner deep dive in joy.

By Rabbi David Evan Markus

Yom Kippur 5784 (2023)

Gut yuntif on this holy Day of Atonement. Our High Holy Day focus has been what we can ask of Judaism and how well Judaism answers. So far, our job description for Judaism has included hope and renewal, identity and empathy, ethics and morality, community and connection.

Today we add teshuvah – repairing our lives, hearts and souls by returning to our best selves, each other and the sacred.

Yom Kippur 5784 (2023)

Gut yuntif on this holy Day of Atonement. Our High Holy Day focus has been what we can ask of Judaism and how well Judaism answers. So far, our job description for Judaism has included hope and renewal, identity and empathy, ethics and morality, community and connection.

Today we add teshuvah – repairing our lives, hearts and souls by returning to our best selves, each other and the sacred.

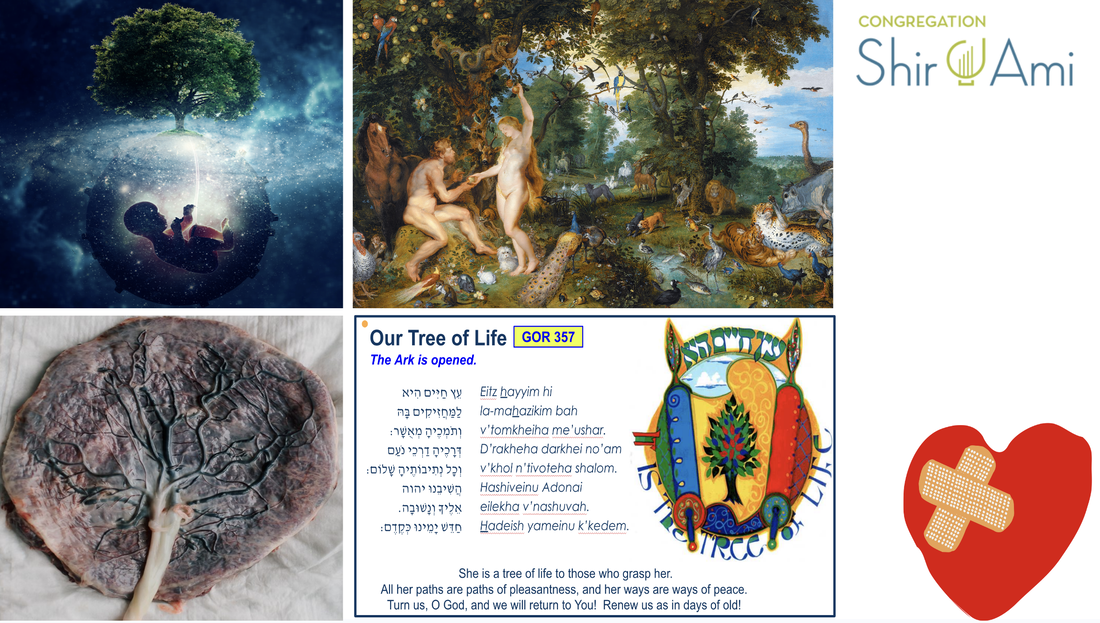

Trees of Life

An old story goes that we all start out with two thickly braided umbilical cords. The first is physical, linked to the placenta sustaining us in the womb: the placenta is literally our tree of life. The second is ethereal, flowing with spiritual sustenance – like Torah, our spiritual tree of life. When we act wrongly against ourselves, another or the world, we cut a tiny fissure in our ethereal cord, causing it to fray and narrow its spiritual flow. When we do teshuvah – make amends, fix a wrong as best we can, change our behavior and apologize – the angel Gabriel repairs our frayed ethereal cord by tying its strands together.

An old story goes that we all start out with two thickly braided umbilical cords. The first is physical, linked to the placenta sustaining us in the womb: the placenta is literally our tree of life. The second is ethereal, flowing with spiritual sustenance – like Torah, our spiritual tree of life. When we act wrongly against ourselves, another or the world, we cut a tiny fissure in our ethereal cord, causing it to fray and narrow its spiritual flow. When we do teshuvah – make amends, fix a wrong as best we can, change our behavior and apologize – the angel Gabriel repairs our frayed ethereal cord by tying its strands together.

If you’ve ever tied a broken string back together, you know that it becomes shorter. So too for our spiritual link. By our teshuvah, the angel Gabriel ties its frayed strands, strengthening the cord and also shortening it. Each time we make amends, we draw closer to God.

One of Judaism’s many beauties is its realism. Realism may seem an unlikely adjective to describe an angel repairing a spiritual cord. Yet whatever our beliefs, the gist is totally realistic about human nature. We fall short; we miss the mark; we fray the ties that bind.

Our story, and Yom Kippur itself, relieve the heavy illusion that spirituality asks for perfection, as if we irreparably fail by falling short. It’s exactly the opposite: 1,500 years ago, the rabbis said (Berakhot 34b), מקום שבעלי תשובה עומדין צדיקים גמורים אינם עומדין / “Where those doing teshuvah stand, not even the totally righteous can stand.” Not even the righteous are righteous because they’re perfect: there’s no such thing. As Proverbs 24:16 puts it, the righteous are righteous not inherently but because they fall and rise up, over and over again.

Now, this isn’t an invitation to swipe that bottom apple from the supermarket fruit display, like playing produce Jenga, then “clean up in aisle five.” But it is to say that teshuvah, our sacred call to return and repair, isn’t second best. It is the best to which any of us can aspire. If so, then society’s perfection ethic is flat wrong. We needn’t hide our missteps and falls, what we’ve done, how we strayed, how we frayed the ties that bind. In truth, we can’t hide – not from ourselves.

If we tune in deeply, we might sense our ethereal cord, how it frays. We might feel it as conscience gnawing, relationships that cooled, where our hearts hardened to dull pain or just get through the day. We might sense where we grew distant, less attuned, less aware of blessings, less fully our best selves, less fully ourselves, less alive.

The fundamental question of Yom Kippur is what we do next.

On Spiritual Bypassing, and Bypass Busting

We humans usually aren’t fans of discomfort, so we cultivate finely honed skills to shift what we feel – often without knowing it. We shift our attention. We philosophize. We seek comfort. All of these are important, and they all have their place in spiritual life.

One of Judaism’s many beauties is its realism. Realism may seem an unlikely adjective to describe an angel repairing a spiritual cord. Yet whatever our beliefs, the gist is totally realistic about human nature. We fall short; we miss the mark; we fray the ties that bind.

Our story, and Yom Kippur itself, relieve the heavy illusion that spirituality asks for perfection, as if we irreparably fail by falling short. It’s exactly the opposite: 1,500 years ago, the rabbis said (Berakhot 34b), מקום שבעלי תשובה עומדין צדיקים גמורים אינם עומדין / “Where those doing teshuvah stand, not even the totally righteous can stand.” Not even the righteous are righteous because they’re perfect: there’s no such thing. As Proverbs 24:16 puts it, the righteous are righteous not inherently but because they fall and rise up, over and over again.

Now, this isn’t an invitation to swipe that bottom apple from the supermarket fruit display, like playing produce Jenga, then “clean up in aisle five.” But it is to say that teshuvah, our sacred call to return and repair, isn’t second best. It is the best to which any of us can aspire. If so, then society’s perfection ethic is flat wrong. We needn’t hide our missteps and falls, what we’ve done, how we strayed, how we frayed the ties that bind. In truth, we can’t hide – not from ourselves.

If we tune in deeply, we might sense our ethereal cord, how it frays. We might feel it as conscience gnawing, relationships that cooled, where our hearts hardened to dull pain or just get through the day. We might sense where we grew distant, less attuned, less aware of blessings, less fully our best selves, less fully ourselves, less alive.

The fundamental question of Yom Kippur is what we do next.

On Spiritual Bypassing, and Bypass Busting

We humans usually aren’t fans of discomfort, so we cultivate finely honed skills to shift what we feel – often without knowing it. We shift our attention. We philosophize. We seek comfort. All of these are important, and they all have their place in spiritual life.

And, authentic spirituality is more than easing discomfort.

When we “use spiritual practices and beliefs to avoid dealing with our painful feelings, unresolved wounds and developmental needs” – when we use spirituality to live away from rather than towards – that’s spiritual bypassing. Spiritual bypassing tends to get in the way of what’s most important – and, it’s normal. We all do it: we all seek comfort.

Why mention spiritual bypassing? Because Yom Kippur rituals seek to interrupt spiritual bypassing – intense time in synagogue, fasting, confessing wrongs that fray our cords, wearing white to evoke our core holiness, or to mimic our burial shrouds as a reminder of our mortality. “Do teshuvah a day before you die,” says Talmud (Shabbat 153a), which means today, for we never really know.

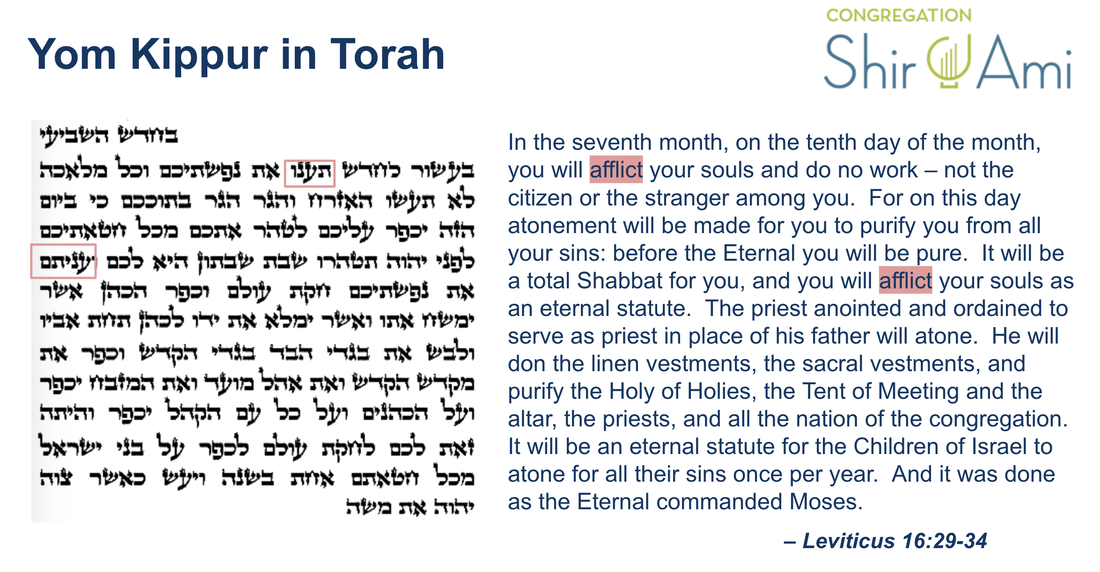

I guess I’m fulfilling the old adage that rabbis comfort the afflicted and, as needed, afflict the comfortable. The thing is, the Yom Kippur I love isn’t really about affliction. Yes, Torah calls Yom Kippur a day on which we “afflict” our souls. Yom Kippur’s bypass-busting traditions come from this understanding; maybe this very sermon is one of those afflictions. And it’s true that Yom Kippur’s harsh edge can prod us to shed hubris, press us to face deep truths, and drive a felt urgency in lives too often dulled by inertia and spiritual bypassing.

But in Hebrew, Torah is written without vowels, and without vowels the word “afflict” also can be read as “answer.” What if Yom Kippur calls us not so much to afflict our souls as to answer them?

When we “use spiritual practices and beliefs to avoid dealing with our painful feelings, unresolved wounds and developmental needs” – when we use spirituality to live away from rather than towards – that’s spiritual bypassing. Spiritual bypassing tends to get in the way of what’s most important – and, it’s normal. We all do it: we all seek comfort.

Why mention spiritual bypassing? Because Yom Kippur rituals seek to interrupt spiritual bypassing – intense time in synagogue, fasting, confessing wrongs that fray our cords, wearing white to evoke our core holiness, or to mimic our burial shrouds as a reminder of our mortality. “Do teshuvah a day before you die,” says Talmud (Shabbat 153a), which means today, for we never really know.

I guess I’m fulfilling the old adage that rabbis comfort the afflicted and, as needed, afflict the comfortable. The thing is, the Yom Kippur I love isn’t really about affliction. Yes, Torah calls Yom Kippur a day on which we “afflict” our souls. Yom Kippur’s bypass-busting traditions come from this understanding; maybe this very sermon is one of those afflictions. And it’s true that Yom Kippur’s harsh edge can prod us to shed hubris, press us to face deep truths, and drive a felt urgency in lives too often dulled by inertia and spiritual bypassing.

But in Hebrew, Torah is written without vowels, and without vowels the word “afflict” also can be read as “answer.” What if Yom Kippur calls us not so much to afflict our souls as to answer them?

With begs a question: What question is your soul asking? If the word “soul” doesn’t land, replace it with conscience, or breath, or life, or history, or God. What is the core question of your life that this holy Yom Kippur asks?

Sometimes we might be reticent to tune in, either because we’re afraid we won’t hear anything, or because we won’t like what we hear, or because we’re not yet prepared to act on our answer.

Diving and Rising Up, Fear and Joy

I think back on the "righteous" of the Book of Proverbs – not the mythic perfect who never fall, but who cultivate courage and resilience to face failures however deep, over and over again. Over time they learn that fraying the cord is unavoidable in human life, and repairing it draws closer to God. Like a diver poised high above a deep pool, they know the water might be cold, but they come to love taking the plunge, diving and rising up again. Diving becomes part of who they are, full of life and full of joy.

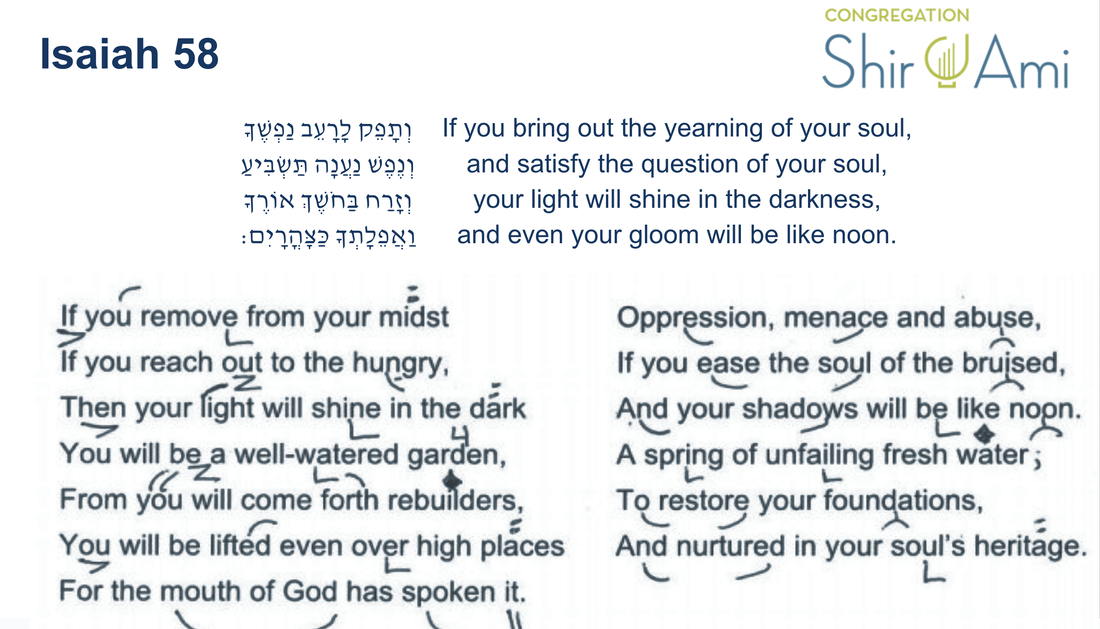

We too can dive deep into what we did and didn’t do, who we are and who we can be, what we must repair, the core oneness of things. It can be joyful. We can answer our souls in joy. Earlier we heard the prophet Isaiah call us into shining. His Hebrew is especially striking:

Sometimes we might be reticent to tune in, either because we’re afraid we won’t hear anything, or because we won’t like what we hear, or because we’re not yet prepared to act on our answer.

Diving and Rising Up, Fear and Joy

I think back on the "righteous" of the Book of Proverbs – not the mythic perfect who never fall, but who cultivate courage and resilience to face failures however deep, over and over again. Over time they learn that fraying the cord is unavoidable in human life, and repairing it draws closer to God. Like a diver poised high above a deep pool, they know the water might be cold, but they come to love taking the plunge, diving and rising up again. Diving becomes part of who they are, full of life and full of joy.

We too can dive deep into what we did and didn’t do, who we are and who we can be, what we must repair, the core oneness of things. It can be joyful. We can answer our souls in joy. Earlier we heard the prophet Isaiah call us into shining. His Hebrew is especially striking:

Yes, there is such bright light, such joy! In ancient days, Yom Kippur wasn’t a day of affliction at all – but a day of joy. Talmud records that no days were “more joyous for Israel than … Yom Kippur” (B.T. Ta’anit 26b).

So why, friends, did Yom Kippur become a day filled with themes of fear and dread? Partly, I think, because ancient rabbis were decent psychologists, literally soul doctors. They already knew what it would take centuries for science to discover: that nature wires humans to be risk averse. It can be inwardly risky to face what we’ve done, heal the hurts we’ve caused, lose face to ourselves and others. Inner change can ask great effort, and inertia is powerful. So, often we need a more powerful force to get us moving and overcome the risk and inertia.

Fear is good for that. It isn’t love of nature or nature’s God that’s starting to galvanize us to quit fossil fuels, but fear of consequence if we don’t. Fear of losing a relationship we cherish can be a powerful inducement to change course and make amends. Guilt is potent, too.

But Yom Kippur’s true core, its true message, isn’t fear or guilt but optimism. Gershom Scholem, scholar of Jewish mysticism, called days like Yom Kippur “plastic” times. These times, Scholem wrote, are “crucial” [ones] when it’s possible to act” with greatest effect because circumstances or times are favorable. A window of opportunity opens: things long stuck can get unstuck.

Yom Kippur is a most precious window of opportunity, a plastic moment. In a world so full of can’t, so gripped by daunting odds, Yom Kippur insists that, yes, we can take the dive. Yes, we can heal ourselves, each other and our world. The very fact of Yom Kippur, its vibrancy over the centuries, this day’s almost cellular power, weaves together all our Jewish superpowers that are our birthright – hope and renewal, identity and empathy, ethics and morality, community and connection. Yom Kippur, Sabbath of Sabbaths, might be our greatest superpower of all for what it says about the human spirit.

There’s still risk. It’s risky to expose our hearts, to face it all, to stand in the full light of truth. And it’s still a dive: the heights are high, the water might be cold, and we’re bound to get wet. But a spirituality that risks nothing is nothing. A spirituality that risks nothing is nothing. And anyone who knows Jewish history knows that history has foisted risk onto us, and that our spiritual ancestors had to become resilient and courageous, a people of audacity, with our Jewish superpowers to thrive amidst risk and do what’s hard when what’s hard is what’s right.

Our path of teshuvah is hard but right, and urgent if we are to live our fullest lives and repair all that has frayed. But in the end, the risk is so much less than we might fear: the bet is rigged. Our teshuvah journey of inner truth, introspection, confession, resolve and repair is just about sure to pay off. The odds are with us: the risk turns out to be mainly illusion. An angel will tie the string: we’re not so far away.

Dr. Leo Buscaglia – the university educator who popularized the loving feel-good philosophy of hugs – came to a similar conclusion from a humanist perspective: “The person who risks nothing, does nothing, has nothing, is nothing and becomes nothing. They may avoid suffering and sorrow – but they simply cannot learn, feel, change, grow or love. Chained by their certitude, they are a slave: they have forfeited their freedom. Only one who risks is truly free.”

It’s time to become free, the real freedom that comes from real transformation.

May this holy Yom Kippur, these precious plastic hours, inspire us to tune in to the deepest question of our soul and heed its call – to know that fear and inertia are little more than the exhilarating height above our diving board. Take the plunge, take the risk, for that truth we’ve been afraid to see and speak. Take the dive, make the change, so we can rise up anew, higher and full of joy, into a year of blessing and true goodness.

And in that merit, may the angels of our better nature, and even the angel we call Gabriel, named messenger of divine strength, re-weave our frayed cords and draw us ever closer to the One we call God.

So why, friends, did Yom Kippur become a day filled with themes of fear and dread? Partly, I think, because ancient rabbis were decent psychologists, literally soul doctors. They already knew what it would take centuries for science to discover: that nature wires humans to be risk averse. It can be inwardly risky to face what we’ve done, heal the hurts we’ve caused, lose face to ourselves and others. Inner change can ask great effort, and inertia is powerful. So, often we need a more powerful force to get us moving and overcome the risk and inertia.

Fear is good for that. It isn’t love of nature or nature’s God that’s starting to galvanize us to quit fossil fuels, but fear of consequence if we don’t. Fear of losing a relationship we cherish can be a powerful inducement to change course and make amends. Guilt is potent, too.

But Yom Kippur’s true core, its true message, isn’t fear or guilt but optimism. Gershom Scholem, scholar of Jewish mysticism, called days like Yom Kippur “plastic” times. These times, Scholem wrote, are “crucial” [ones] when it’s possible to act” with greatest effect because circumstances or times are favorable. A window of opportunity opens: things long stuck can get unstuck.

Yom Kippur is a most precious window of opportunity, a plastic moment. In a world so full of can’t, so gripped by daunting odds, Yom Kippur insists that, yes, we can take the dive. Yes, we can heal ourselves, each other and our world. The very fact of Yom Kippur, its vibrancy over the centuries, this day’s almost cellular power, weaves together all our Jewish superpowers that are our birthright – hope and renewal, identity and empathy, ethics and morality, community and connection. Yom Kippur, Sabbath of Sabbaths, might be our greatest superpower of all for what it says about the human spirit.

There’s still risk. It’s risky to expose our hearts, to face it all, to stand in the full light of truth. And it’s still a dive: the heights are high, the water might be cold, and we’re bound to get wet. But a spirituality that risks nothing is nothing. A spirituality that risks nothing is nothing. And anyone who knows Jewish history knows that history has foisted risk onto us, and that our spiritual ancestors had to become resilient and courageous, a people of audacity, with our Jewish superpowers to thrive amidst risk and do what’s hard when what’s hard is what’s right.

Our path of teshuvah is hard but right, and urgent if we are to live our fullest lives and repair all that has frayed. But in the end, the risk is so much less than we might fear: the bet is rigged. Our teshuvah journey of inner truth, introspection, confession, resolve and repair is just about sure to pay off. The odds are with us: the risk turns out to be mainly illusion. An angel will tie the string: we’re not so far away.

Dr. Leo Buscaglia – the university educator who popularized the loving feel-good philosophy of hugs – came to a similar conclusion from a humanist perspective: “The person who risks nothing, does nothing, has nothing, is nothing and becomes nothing. They may avoid suffering and sorrow – but they simply cannot learn, feel, change, grow or love. Chained by their certitude, they are a slave: they have forfeited their freedom. Only one who risks is truly free.”

It’s time to become free, the real freedom that comes from real transformation.

May this holy Yom Kippur, these precious plastic hours, inspire us to tune in to the deepest question of our soul and heed its call – to know that fear and inertia are little more than the exhilarating height above our diving board. Take the plunge, take the risk, for that truth we’ve been afraid to see and speak. Take the dive, make the change, so we can rise up anew, higher and full of joy, into a year of blessing and true goodness.

And in that merit, may the angels of our better nature, and even the angel we call Gabriel, named messenger of divine strength, re-weave our frayed cords and draw us ever closer to the One we call God.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed