Shanah tovah! I hope this new year has dawned bright and full of hope for you and your beloveds.

How ironic that the first Torah portion of the new year is nearly Torah's last. How ironic that this Torah portion is the swan song of Moses as he faces his fast impending death.

Ironic – and, with Yom Kippur up next, utterly right.

How ironic that the first Torah portion of the new year is nearly Torah's last. How ironic that this Torah portion is the swan song of Moses as he faces his fast impending death.

Ironic – and, with Yom Kippur up next, utterly right.

Swan Song. Last call. Closing time. Everything of this earth eventually must end.

We know it, but this truth hiding in plain sight usually isn't polite conversation. Though humans appear to be Earth's only species conscious of our ultimate mortality, we spend much of our lives pretending otherwise – as if we could outrun the inevitable we know to be so.

Along come the High Holy Days and its calls to higher meaning – including our mortality. The Unetaneh Tokef liturgy of Rosh Hashanah evokes a Book of Life and Book of Death to smash the inertia in our lives. Yom Kippur thins the veil further. Some will fast to deny the body. On Kol Nidre and Yom Kippur, some wear white – whether to remind us of our essential core that includes every color, symbolize ascent above routine time, map to the angelic sphere or, soberingly, remind us of our mortality. (Jews traditionally are buried in simple white shrouds.) In essence, on Yom Kippur we rehearse our inevitable death.

Why? Because consciousness of our limited time not only can smash the inertia in our lives, but also impel us to do teshuvah. Judaism’s ethical tradition (Pirkei Avot 2:10) and rabbinic tradition (B.T. Shabbat 153a) both call us to do teshuvah – return, repent, renew, re-vision our lives – not on the day we die but the day before we die. We don’t know when that day will be, of course, so the day for teshuvah is today.

Now Torah herself joins this inertia smashing project, as a prelude to Yom Kippur. Parashat Ha'azinu is mainly Moses' last words to the Children of Israel, a poignant poem-song downloading the core of his life for posterity. He begins (Deut. 32:1-4):

We know it, but this truth hiding in plain sight usually isn't polite conversation. Though humans appear to be Earth's only species conscious of our ultimate mortality, we spend much of our lives pretending otherwise – as if we could outrun the inevitable we know to be so.

Along come the High Holy Days and its calls to higher meaning – including our mortality. The Unetaneh Tokef liturgy of Rosh Hashanah evokes a Book of Life and Book of Death to smash the inertia in our lives. Yom Kippur thins the veil further. Some will fast to deny the body. On Kol Nidre and Yom Kippur, some wear white – whether to remind us of our essential core that includes every color, symbolize ascent above routine time, map to the angelic sphere or, soberingly, remind us of our mortality. (Jews traditionally are buried in simple white shrouds.) In essence, on Yom Kippur we rehearse our inevitable death.

Why? Because consciousness of our limited time not only can smash the inertia in our lives, but also impel us to do teshuvah. Judaism’s ethical tradition (Pirkei Avot 2:10) and rabbinic tradition (B.T. Shabbat 153a) both call us to do teshuvah – return, repent, renew, re-vision our lives – not on the day we die but the day before we die. We don’t know when that day will be, of course, so the day for teshuvah is today.

Now Torah herself joins this inertia smashing project, as a prelude to Yom Kippur. Parashat Ha'azinu is mainly Moses' last words to the Children of Israel, a poignant poem-song downloading the core of his life for posterity. He begins (Deut. 32:1-4):

Give ear, O heavens! Let me speak!

Let the earth hear the words I utter!

May my discourse descend like rain,

My speech distill like dew,

Like showers on young growth,

Like droplets on the grass.

For the Name of YHVH I proclaim:

Give glory to our God!

The Rock! – whose deeds are perfect,

For all God’s ways are just:

A faithful God, never false,

True and upright.

Let the earth hear the words I utter!

May my discourse descend like rain,

My speech distill like dew,

Like showers on young growth,

Like droplets on the grass.

For the Name of YHVH I proclaim:

Give glory to our God!

The Rock! – whose deeds are perfect,

For all God’s ways are just:

A faithful God, never false,

True and upright.

Moses' poignant words continue that his people will stray (as we have, over and over again), and that our spiritual return will be the ultimate vindication – just in time for Yom Kippur. Plus, for extra impact, the italicized words above are core for Jewish funerals. Not subtle.

The real point is how we respond to these many allusion to mortality – for Moses, ultimately for everyone, and ultimately for us. We can do so with resentment, anger and fear, or we can do it with love and joy.

Love and joy? On Yom Kippur? Yep.

While rabbinic liturgies of Yom Kippur evolved to evoke fear as a catalyst for teshuvah, the original Yom Kippur was all about joy. On the day that became Yom Kippur, Moses received the second set of Tablets atop Sinai after the Golden Calf incident. Yom Kippur became the day of forgiveness and second chances. In that spirit, in ancient days "There were no days of joy in Israel greater than ... Yom Kippur" (Mishneh Taanit 4:8). The day was so full of joy that it even became a day to dance in whites and find love in the vineyards.

Yes, Yom Kippur is deep: it's vital that we confront our mortality and work this awareness deeply into our lives, so that we can live our fullest lives. On Yom Kippur, Jews worldwide will wear white – perhaps from ancient days when Yom Kippur was like Valentine's Day, but also to rehearse death (when traditionally Jews are buried in a white shroud). We must confront our mortality to impel us to live our fullest lives. And at the very same time, the same Yom Kippur that somehow became about dread and judgment also is a day for emotional and spiritual height – joy and awe, not fear. As Nahman of Breslov famously taught:

The real point is how we respond to these many allusion to mortality – for Moses, ultimately for everyone, and ultimately for us. We can do so with resentment, anger and fear, or we can do it with love and joy.

Love and joy? On Yom Kippur? Yep.

While rabbinic liturgies of Yom Kippur evolved to evoke fear as a catalyst for teshuvah, the original Yom Kippur was all about joy. On the day that became Yom Kippur, Moses received the second set of Tablets atop Sinai after the Golden Calf incident. Yom Kippur became the day of forgiveness and second chances. In that spirit, in ancient days "There were no days of joy in Israel greater than ... Yom Kippur" (Mishneh Taanit 4:8). The day was so full of joy that it even became a day to dance in whites and find love in the vineyards.

Yes, Yom Kippur is deep: it's vital that we confront our mortality and work this awareness deeply into our lives, so that we can live our fullest lives. On Yom Kippur, Jews worldwide will wear white – perhaps from ancient days when Yom Kippur was like Valentine's Day, but also to rehearse death (when traditionally Jews are buried in a white shroud). We must confront our mortality to impel us to live our fullest lives. And at the very same time, the same Yom Kippur that somehow became about dread and judgment also is a day for emotional and spiritual height – joy and awe, not fear. As Nahman of Breslov famously taught:

| כָּל הָעוֹלָם כּוּלוֹ גֶשֶׁר צָר מְאוֹד וְהָעִיקַר לֹא לְפַחֵד כְּלַל | The whole entire world is a narrow bridge And the point is not to make ourselves afraid. |

Human life is a bridge between pre-life and after-life: we're all on that narrow bridge together. All that we know, and all that we are and ever will be, is on that bridge. And like traversing a physical bridge across a river, with faith in the bridge's firm fixing to its two ends we can cross without fear – and enjoy the view. It's a heck of a view!

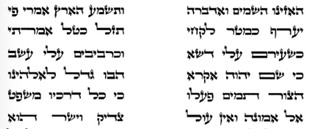

Look again at Torah's calligraphy for this pivotal portion. Unlike most of Torah, Ha'azinu is scribed in two parallel columns. This rare calligraphy connotes a poem, which is what Moses' swan song is – and also a chasm between the two columns. Our lives are the open space between them. Yom Kippur especially is that open space.

Learning to love this vast openness, and its limits, can be a tremendous source of joy and meaning in our lives. And in that love and meaning is the beginning of most everything else.

In the end, Moses' death is not the end – for even as Torah soon will end, immediately we will begin again. Joshua will lead the people forward, and in one breath we'll begin anew with God beginning to begin creation, and a void, and a first light. The light never, ever, goes out.

May this Yom Kippur inspire us to sing and even dance on our narrow bridge, to transform our lives for good.

Look again at Torah's calligraphy for this pivotal portion. Unlike most of Torah, Ha'azinu is scribed in two parallel columns. This rare calligraphy connotes a poem, which is what Moses' swan song is – and also a chasm between the two columns. Our lives are the open space between them. Yom Kippur especially is that open space.

Learning to love this vast openness, and its limits, can be a tremendous source of joy and meaning in our lives. And in that love and meaning is the beginning of most everything else.

In the end, Moses' death is not the end – for even as Torah soon will end, immediately we will begin again. Joshua will lead the people forward, and in one breath we'll begin anew with God beginning to begin creation, and a void, and a first light. The light never, ever, goes out.

May this Yom Kippur inspire us to sing and even dance on our narrow bridge, to transform our lives for good.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed