If art and beauty are in the eye of the beholder, then what about spirituality and community? And when we feel disconnected from spirituality and community – as everyone sometimes does – then what?

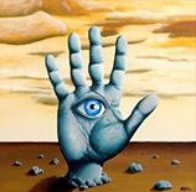

This week’s Torah portion (Re'eh) invites us to see that one of the most powerful tools of spirituality concerns "how we see" what we see. If we look closely, we might see that spirituality leads less through our eyes than our hands.

This week’s Torah portion (Re'eh) invites us to see that one of the most powerful tools of spirituality concerns "how we see" what we see. If we look closely, we might see that spirituality leads less through our eyes than our hands.

Classical Judaism is a tradition and culture of doing. This week's Torah portion records that three times each year – at the festivals of Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot – our spiritual ancestors would bring to the Temple in Jerusalem offering and gifts. These might have been agricultural goods, or money for easier travel. This festival journey to Jerusalem and the communal gatherings there helped define Jewish identity. Then as now, Judaism was about generosity, coming together in community, structuring the year around that purpose, and harnessing individuality to serve the holy collectively.

For the people's presence amidst the Presence believed to dwell there (hence the Hebrew word Shekhinah, "indwelling presence"), Torah called each person to bring “one’s own gift according to the blessing that YHVH your God bestowed” on them (Deut. 16:17). In its day, this notion was astonishingly forward-thinking. It was radically “democratic” for everyone to give something, and “progressive” to gauge the amount to one's ability to give.

For community governance, democratic progressivism is a big deal. The healthiest spiritual community is one that enfolds everyone without exception, in which everyone participates by giving what they can without exception (whether volunteerism, stuff or financial support), and where those having more give more willingly from their hearts.

So far, so good. But then Torah seems to repeat its calling to give, and does so with a curious phrase: ולא יראה את פני יהו׳׳ה ריקם (Deut. 16:16). How we translate this phrase makes a huge difference to how we understand Torah's call to spirituality both individually and communally.

This phrase’s most common English rendering is, “And none will be seen before God’s face empty-handed” – in ancient parlance, just repeating that everyone should bring something. But Torah doesn't mince words and has no need to repeat itself – so in Jewish thought this phrase must mean something more.

Another re-translation is: “And none will see God’s face if they are empty-handed.”

But how can this be? We already saw that, in Torah's understanding, nobody is inherently empty-handed: everyone has a gift to bring “according to the blessing that YHVH your God bestowed," and everyone must bring something.

Perhaps Torah is teaching us not that the spiritual journey requires an admission ticket, but that anyone who feels empty-handed – who feels that they lack a genuine and valuable gift to bring into community – inherently will be diminished in experiencing the holiness we call God. We learn that our capacity to see and experience holiness in our lives, and in our world, depends at least partly on what we give and what we feel ourselves capable of giving. And by Torah’s words, this isn’t only an economic issue but also, mainly, a spiritual issue.

Put differently, the eye is in the hand of the beholder.

Torah doubles down in a second way. Torah’s word for “empty-handed” (ריקם / reikam) most literally means “vainly” or “emptily,” meaning without effect. When we feel ourselves to have no effect, to live vainly or emptily, that’s when we tend to pull inward, isolate from spiritual community and not give. It can become a self-fulfilling prophesy: our hands might as well be empty, and then our hearts feel empty.

Torah is teaching us that it need not be so. We all can bring our selves – our most precious commodity – into community and into the world. That means our love, patience, effort, time, volunteerism, charity, compassion and more. In Torah's ancient jargon, these are very much in our hands to give, according to the blessings in our lives.

And what's more, the more we see our lives as blessed, even in the smallest ways, however great the difficulties we face, the more we're likely to feel abundant. (That's why gratitude, and spiritual practices of gratitude, can be so powerful – and a key reason that Jewish blessings center these practices in ritual life.) It's this felt sense of abundance, and with it a corresponding felt sense of responsibility, that help inspire us to give time, money and care. And the more we give these in measure with capacity, the fuller our hearts will feel, the fuller our hands will feel, and the more goodness we're likely to perceive.

It’s a virtuous cycle, this cycle of virtue. Most things in healthy community are – and that's the point Torah is making. The more we commit to tangible acts of social justice, the more we connect, the more we see results, the more likeminded and like-hearted people join us. The more a community commits to learning (or most anything else), the more its culture takes hold, and the more its culture will attract more.

The eye really is in the hand of the beholder, and the virtuous cycle even includes the One we call God. In the words of the Psalmist (Psalm 90:16-17):

For the people's presence amidst the Presence believed to dwell there (hence the Hebrew word Shekhinah, "indwelling presence"), Torah called each person to bring “one’s own gift according to the blessing that YHVH your God bestowed” on them (Deut. 16:17). In its day, this notion was astonishingly forward-thinking. It was radically “democratic” for everyone to give something, and “progressive” to gauge the amount to one's ability to give.

For community governance, democratic progressivism is a big deal. The healthiest spiritual community is one that enfolds everyone without exception, in which everyone participates by giving what they can without exception (whether volunteerism, stuff or financial support), and where those having more give more willingly from their hearts.

So far, so good. But then Torah seems to repeat its calling to give, and does so with a curious phrase: ולא יראה את פני יהו׳׳ה ריקם (Deut. 16:16). How we translate this phrase makes a huge difference to how we understand Torah's call to spirituality both individually and communally.

This phrase’s most common English rendering is, “And none will be seen before God’s face empty-handed” – in ancient parlance, just repeating that everyone should bring something. But Torah doesn't mince words and has no need to repeat itself – so in Jewish thought this phrase must mean something more.

Another re-translation is: “And none will see God’s face if they are empty-handed.”

But how can this be? We already saw that, in Torah's understanding, nobody is inherently empty-handed: everyone has a gift to bring “according to the blessing that YHVH your God bestowed," and everyone must bring something.

Perhaps Torah is teaching us not that the spiritual journey requires an admission ticket, but that anyone who feels empty-handed – who feels that they lack a genuine and valuable gift to bring into community – inherently will be diminished in experiencing the holiness we call God. We learn that our capacity to see and experience holiness in our lives, and in our world, depends at least partly on what we give and what we feel ourselves capable of giving. And by Torah’s words, this isn’t only an economic issue but also, mainly, a spiritual issue.

Put differently, the eye is in the hand of the beholder.

Torah doubles down in a second way. Torah’s word for “empty-handed” (ריקם / reikam) most literally means “vainly” or “emptily,” meaning without effect. When we feel ourselves to have no effect, to live vainly or emptily, that’s when we tend to pull inward, isolate from spiritual community and not give. It can become a self-fulfilling prophesy: our hands might as well be empty, and then our hearts feel empty.

Torah is teaching us that it need not be so. We all can bring our selves – our most precious commodity – into community and into the world. That means our love, patience, effort, time, volunteerism, charity, compassion and more. In Torah's ancient jargon, these are very much in our hands to give, according to the blessings in our lives.

And what's more, the more we see our lives as blessed, even in the smallest ways, however great the difficulties we face, the more we're likely to feel abundant. (That's why gratitude, and spiritual practices of gratitude, can be so powerful – and a key reason that Jewish blessings center these practices in ritual life.) It's this felt sense of abundance, and with it a corresponding felt sense of responsibility, that help inspire us to give time, money and care. And the more we give these in measure with capacity, the fuller our hearts will feel, the fuller our hands will feel, and the more goodness we're likely to perceive.

It’s a virtuous cycle, this cycle of virtue. Most things in healthy community are – and that's the point Torah is making. The more we commit to tangible acts of social justice, the more we connect, the more we see results, the more likeminded and like-hearted people join us. The more a community commits to learning (or most anything else), the more its culture takes hold, and the more its culture will attract more.

The eye really is in the hand of the beholder, and the virtuous cycle even includes the One we call God. In the words of the Psalmist (Psalm 90:16-17):

| יֵרָאֶ֣ה אֶל־עֲבָדֶ֣יךָ פָעֳלֶ֑ךָ וַ֝הֲדָרְךָ֗ עַל־בְּנֵיהֶֽם׃ וִיהִ֤י ׀ נֹ֤עַם אֲדֹנָ֥י אֱלֹהֵ֗ינוּ עָ֫לֵ֥ינוּ וּמַעֲשֵׂ֣ה יָ֭דֵינוּ כּוֹנְנָ֥ה עָלֵ֑ינוּ וּֽמַעֲשֵׂ֥ה יָ֝דֵ֗ינוּ כּוֹנְנֵֽהוּ׃ | "Let Your deeds be seen by Your servants, and Your glory by their children. May the beauty of YHVH our God be on us and establish the work of our hands, And may the works of our hands establish God." |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed