| For my first weekly dvar Torah as rabbi and spiritual leader of Congregation Shir Ami, let's talk about spearing people through the guts while they have sex on the altar. Seriously? That's the context of how Parshat Pinchas begins. (Isn't it every rabbi's dream to begin serving a spiritual community community with this?) Then again, often Torah embeds beautiful worlds of wonder, depth and redemptive meaning precisely in her dark alleys. Here, too – and exactly on time for Judaism's spiritual calendar. |

By Rabbi David Evan Markus

Parashat Pinchas 5783 (2023)

Our desert-wandering spiritual ancestors wander away from God yet again. Pinchas, grandson of Aaron the High Priest, sees a Jew (Zimri) and Midianite (Kozbi) having sex on the altar – a Midianite fertility practice consistent with their ancient spiritual practices, but not Jewish ones. Pinchas responds by harpooning them (Num. 25:6-9).

Parashat Pinchas 5783 (2023)

Our desert-wandering spiritual ancestors wander away from God yet again. Pinchas, grandson of Aaron the High Priest, sees a Jew (Zimri) and Midianite (Kozbi) having sex on the altar – a Midianite fertility practice consistent with their ancient spiritual practices, but not Jewish ones. Pinchas responds by harpooning them (Num. 25:6-9).

Torah then records that YHVH – an English rendition of יהו׳׳ה, the four-letter Tetragrammaton, the Ineffable Name of the Nameless One we call God – said to Moses (Num. 25:11-12):

פִּֽינְחָ֨ס בֶּן־אֶלְעָזָ֜ר בֶּן־אַהֲרֹ֣ן הַכֹּהֵ֗ן הֵשִׁ֤יב אֶת־חֲמָתִי֙ מֵעַ֣ל בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל בְּקַנְא֥וֹ אֶת־קִנְאָתִ֖י בְּתוֹכָ֑ם וְלֹא־כִלִּ֥יתִי אֶת־בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל בְּקִנְאָתִֽי׃ לָכֵ֖ן אֱמֹ֑ר הִנְנִ֨י נֹתֵ֥ן ל֛וֹ אֶת־בְּרִיתִ֖י שָׁלֽוֹם׃

Pinchas, son of Elezar son of Aaron the Priest, turned back My wrath from the Children of Israel by his zealotry, so My zealotry among them would not wipe out the Children of Israel in My passion. Therefore say [to him], "Behold, I give you my Covenant of Shalom."

Huh? God rewarded Pinchas for slaughtering two people? On the altar? In cold blood?

So imagined tradition's commentators, who perhaps were zealous to protect and celebrate a pietous Judaism. Rashi (11th century) wrote that a God grateful for Pinchas' "kindness" had "peaceful feelings" for him. Ibn Ezra (12th century) went further, writing that God rewarded Pinchas and his descendants with the Aaronic priesthood. The Sforno (16th century) wrote that Pinchas' reward of a "Covenant of Shalom" was peace with the Angel of Death, so that Pinchas would have an exceedingly long life.

If it doesn't sit right with you, you're not alone. It doesn't sit right with me either – and apparently not with the Masoretes, ritual scribes of 700s-1000s CE who finalized how Torah scrolls are written. To them, the "Covenant of Shalom" implied far more than any surface meaning – and certainly far more than a reward.

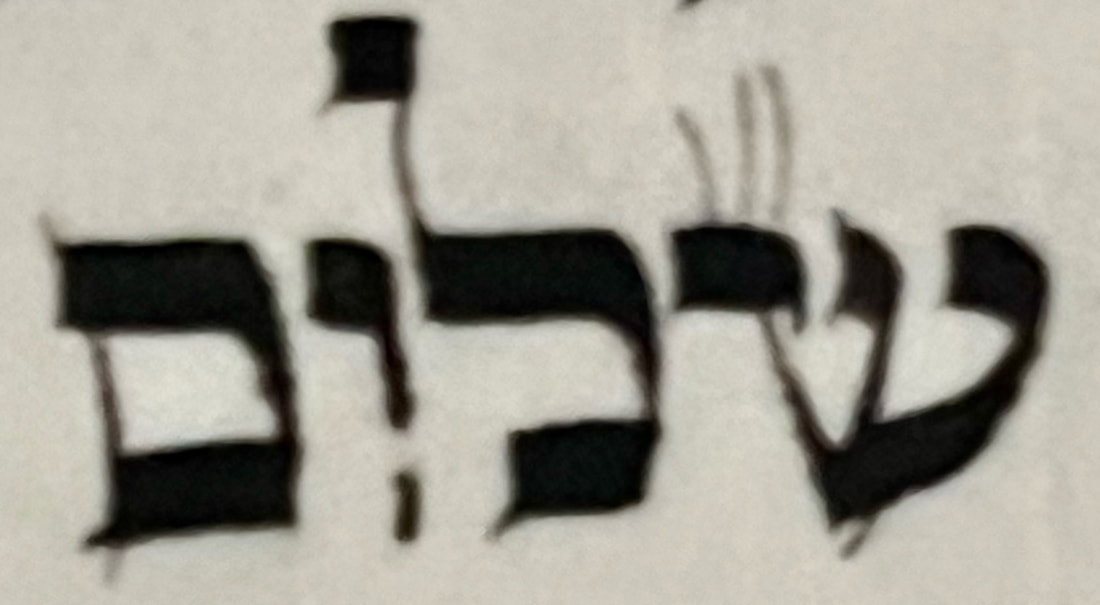

So when the Masoretes scribed the word Shalom, they broke it. Look at any Torah scroll, and the vertical letter vav in the word Shalom (שלום) – which looks like a spear – is sliced in two:

פִּֽינְחָ֨ס בֶּן־אֶלְעָזָ֜ר בֶּן־אַהֲרֹ֣ן הַכֹּהֵ֗ן הֵשִׁ֤יב אֶת־חֲמָתִי֙ מֵעַ֣ל בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל בְּקַנְא֥וֹ אֶת־קִנְאָתִ֖י בְּתוֹכָ֑ם וְלֹא־כִלִּ֥יתִי אֶת־בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל בְּקִנְאָתִֽי׃ לָכֵ֖ן אֱמֹ֑ר הִנְנִ֨י נֹתֵ֥ן ל֛וֹ אֶת־בְּרִיתִ֖י שָׁלֽוֹם׃

Pinchas, son of Elezar son of Aaron the Priest, turned back My wrath from the Children of Israel by his zealotry, so My zealotry among them would not wipe out the Children of Israel in My passion. Therefore say [to him], "Behold, I give you my Covenant of Shalom."

Huh? God rewarded Pinchas for slaughtering two people? On the altar? In cold blood?

So imagined tradition's commentators, who perhaps were zealous to protect and celebrate a pietous Judaism. Rashi (11th century) wrote that a God grateful for Pinchas' "kindness" had "peaceful feelings" for him. Ibn Ezra (12th century) went further, writing that God rewarded Pinchas and his descendants with the Aaronic priesthood. The Sforno (16th century) wrote that Pinchas' reward of a "Covenant of Shalom" was peace with the Angel of Death, so that Pinchas would have an exceedingly long life.

If it doesn't sit right with you, you're not alone. It doesn't sit right with me either – and apparently not with the Masoretes, ritual scribes of 700s-1000s CE who finalized how Torah scrolls are written. To them, the "Covenant of Shalom" implied far more than any surface meaning – and certainly far more than a reward.

So when the Masoretes scribed the word Shalom, they broke it. Look at any Torah scroll, and the vertical letter vav in the word Shalom (שלום) – which looks like a spear – is sliced in two:

The Masoretes couldn't bear valorizing murder, much less by divine reward – and neither can we. History is littered with intolerably many murders by blood and slaughters of spirit – misogyny, racism, homophobia, antisemitism, Islamophobia – perpetrated in God's name.

So Torah slices the vav, urging us to delve far deeper than Torah's surface meaning.

Could it be that God wasn't rewarding Pinchas so much as calming his excesses and, as in Torah's calligraphy, snapping Pinchas' spear? How often have we seen folks whose rage or zeal gets the best of them? How often have we lost our best selves to fury's power? (To be clear, anger can be productive and even sacred – as an impulse to name and correct wrong behavior, act for social justice and engage in self-care. But as Alan Morinis wrote in Everyday Holiness, there's a world of difference between anger and hostility.)

And perhaps God was deeply pained by Pinchas' impulsivity. So wrote 20th century Ukrainian rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin: "The vav is sliced because this 'peace' came by spilling blood. The Holy Blessed One does not rejoice even in this downfall of evil. Thus, God's pain is expressed by slicing the vav of shalom, which is the very Name of God."

Take that in. Ancient tradition offers that shalom is a Name of God – not the shalom of "hello," "goodbye" and "peace," but the shalom of shleimut (wholeness, totality). When zealotry drives us to act with hostility – however right we feel in the moment, even if we think we're acting righteously, even if we believe that God would approve! – most likely our zealotry splits us from a part of ourselves. We split from the essence of holiness by slicing the Name of God.

Understood this way, Pinchas comes not to valorize but to challenge us to rethink what we know and how we know it, to look beyond surface appearance, and to cast a wise eye inward toward the bits of Pinchas we're all prone to carry. By heeding this call, we can move toward healing ourselves, each other, the world, and perhaps even Torah's broken vav itself.

This call to introspection comes exactly on time: Judaism's 10-week ramp to Rosh Hashanah and the Season of Teshuvah (repentance, return) begins this week. (Shameless plug: Shir Ami's seven-session series, "This is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared: A Journey into the Season of Meaning," starts July 11. Click here for information and registration.

*

Another thing: This approach to Torah doesn't ask or even allow blind obeisance, but rather asks engagement and discernment. There's far more to Torah than meets the eye. Torah is teaching us to interpret, reinterpret, wrestle, and even be ready to slice a letter.

"Slice Torah?" you might ask. "Our new rabbi believes in that?"

Yes, yes I do – for the right reasons. And so does Torah herself.

Torah's earlier chapters laid out a first system for inheritance. Reflecting the socioeconomics of the Mideast 3,500-ish years ago, those first laws provided for only men to inherit. But in this week's pareshah, the five daughters of Tzelofchad (who died without sons) urge Moses that their father's legacy shouldn't disappear by dint of gender. The five women – Mahlah, Noah, Moglah, Milkah and Tirzah – tell Moses that the Five Books of Moses were wrong.

And God agrees! God tells Moses to overrule Torah, because the five women were correct to challenge an unfair status quo (Num. 27:1-8). And by challenging an unfair status quo – even in Torah herself – the daughters of Tzelofchad made for more shleimut (wholeness). (The "fix" was still gender-discriminatory, so Talmud and modernity would need to finish the job.)

*

Sometimes peace isn't peaceful. Sometimes doing right is more important than keeping peace. Other times, healthy anger can ferment into destructive hostility. Spiritual life calls us to seek balance between zeal and zealotry, justice and peace, right and righteousness. It's the journey of a lifetime – and particularly the journey of the Jewish spiritual season now beginning.

Here we go.

So Torah slices the vav, urging us to delve far deeper than Torah's surface meaning.

Could it be that God wasn't rewarding Pinchas so much as calming his excesses and, as in Torah's calligraphy, snapping Pinchas' spear? How often have we seen folks whose rage or zeal gets the best of them? How often have we lost our best selves to fury's power? (To be clear, anger can be productive and even sacred – as an impulse to name and correct wrong behavior, act for social justice and engage in self-care. But as Alan Morinis wrote in Everyday Holiness, there's a world of difference between anger and hostility.)

And perhaps God was deeply pained by Pinchas' impulsivity. So wrote 20th century Ukrainian rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin: "The vav is sliced because this 'peace' came by spilling blood. The Holy Blessed One does not rejoice even in this downfall of evil. Thus, God's pain is expressed by slicing the vav of shalom, which is the very Name of God."

Take that in. Ancient tradition offers that shalom is a Name of God – not the shalom of "hello," "goodbye" and "peace," but the shalom of shleimut (wholeness, totality). When zealotry drives us to act with hostility – however right we feel in the moment, even if we think we're acting righteously, even if we believe that God would approve! – most likely our zealotry splits us from a part of ourselves. We split from the essence of holiness by slicing the Name of God.

Understood this way, Pinchas comes not to valorize but to challenge us to rethink what we know and how we know it, to look beyond surface appearance, and to cast a wise eye inward toward the bits of Pinchas we're all prone to carry. By heeding this call, we can move toward healing ourselves, each other, the world, and perhaps even Torah's broken vav itself.

This call to introspection comes exactly on time: Judaism's 10-week ramp to Rosh Hashanah and the Season of Teshuvah (repentance, return) begins this week. (Shameless plug: Shir Ami's seven-session series, "This is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared: A Journey into the Season of Meaning," starts July 11. Click here for information and registration.

*

Another thing: This approach to Torah doesn't ask or even allow blind obeisance, but rather asks engagement and discernment. There's far more to Torah than meets the eye. Torah is teaching us to interpret, reinterpret, wrestle, and even be ready to slice a letter.

"Slice Torah?" you might ask. "Our new rabbi believes in that?"

Yes, yes I do – for the right reasons. And so does Torah herself.

Torah's earlier chapters laid out a first system for inheritance. Reflecting the socioeconomics of the Mideast 3,500-ish years ago, those first laws provided for only men to inherit. But in this week's pareshah, the five daughters of Tzelofchad (who died without sons) urge Moses that their father's legacy shouldn't disappear by dint of gender. The five women – Mahlah, Noah, Moglah, Milkah and Tirzah – tell Moses that the Five Books of Moses were wrong.

And God agrees! God tells Moses to overrule Torah, because the five women were correct to challenge an unfair status quo (Num. 27:1-8). And by challenging an unfair status quo – even in Torah herself – the daughters of Tzelofchad made for more shleimut (wholeness). (The "fix" was still gender-discriminatory, so Talmud and modernity would need to finish the job.)

*

Sometimes peace isn't peaceful. Sometimes doing right is more important than keeping peace. Other times, healthy anger can ferment into destructive hostility. Spiritual life calls us to seek balance between zeal and zealotry, justice and peace, right and righteousness. It's the journey of a lifetime – and particularly the journey of the Jewish spiritual season now beginning.

Here we go.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed