Imagine what our world would be if we extended ourselves just a bit more beyond what most frightens or upsets us. Imagine what our world would be if we each stretched just a bit more into the equality, kindness, gratitude, Godwrestling and stranger love that are the core callings of our ancestral identity. It starts with us. It starts today.

We can choose to let our suffering, jealousy and fear harden us. Or we can let them soften us, and remind us that we know the Other’s heart because we’ve been the Other, too. Empathy is healing for most every felt sense of Otherness, and most especially for our own.

We can choose to let our suffering, jealousy and fear harden us. Or we can let them soften us, and remind us that we know the Other’s heart because we’ve been the Other, too. Empathy is healing for most every felt sense of Otherness, and most especially for our own.

Shabbat shalom and shanah tovah! It’s a joy to be together.

Last night we launched our High Holy Days by discerning what we can ask of our Judaism, and how well Judaism answers. I floated six pairs of goals for a Judaism job description. We began with hope that inspired our ancestors to survive, thrive, defy odds and work miracles. We are to be hope mongers – not just optimists, or blind to challenges, but activists that we can renew ourselves and our world. (Click here for my Erev Rosh Hashanah sermon.)

Last night we launched our High Holy Days by discerning what we can ask of our Judaism, and how well Judaism answers. I floated six pairs of goals for a Judaism job description. We began with hope that inspired our ancestors to survive, thrive, defy odds and work miracles. We are to be hope mongers – not just optimists, or blind to challenges, but activists that we can renew ourselves and our world. (Click here for my Erev Rosh Hashanah sermon.)

To hope and renewal, today we add identity and empathy to our Jewish job description. And to get us started, a quick story.

Spiritual Experiences in Unlikely Places

Spiritual Experiences in Unlikely Places

I am a believer in painless dentistry. I say so because recently I needed dental work, so off I went to the painless dentist. First there was gel to numb my gums. Then novocaine shots so I wouldn’t feel deeper shots. Then deeper shots.

Then nitrous oxide gas.

Then nitrous oxide gas.

Soon my mind was a hot air balloon high in a clear blue sky. The overhead dental light was the sun, which became the primordial light of creation that shines on me, and you, and everyone.

I am a cheap date.

Maybe you’re unfazed that I describe a spiritual experience: after all, I am a rabbi. But I’m also a lawyer by training and a judicial officer by trade: I deal in logic and evidence. And besides, a dentist chair is the last place I’d think to call spiritual. Yet the experience stays with me: the light is as brilliantly bright and real to me now as it was then.

So there I was, in the dentist chair, instruments in my mouth, the light of creation shining. I still vividly recall how deep questions had clear intuitive answers, including this one:

“Are my teeth Jewish?”

My nitrous gas logic reasoned that teeth are inanimate objects and thus couldn’t be any more Jewish than a spoon or a tree – which begged other questions. What makes me Jewish? What makes any of us who we are, or who we claim to be? Who are we really?

Identity and Empathy

These are our subjects today. One of Judaism’s jobs is to shape our identity – to teach us who we are and who we’re called to be, to imbue a sense of belonging and cohesion. And on Rosh Hashanah, the start of our year and ritual start of creation and peoplehood, it’s worth reaffirming those first principles.

I am a cheap date.

Maybe you’re unfazed that I describe a spiritual experience: after all, I am a rabbi. But I’m also a lawyer by training and a judicial officer by trade: I deal in logic and evidence. And besides, a dentist chair is the last place I’d think to call spiritual. Yet the experience stays with me: the light is as brilliantly bright and real to me now as it was then.

So there I was, in the dentist chair, instruments in my mouth, the light of creation shining. I still vividly recall how deep questions had clear intuitive answers, including this one:

“Are my teeth Jewish?”

My nitrous gas logic reasoned that teeth are inanimate objects and thus couldn’t be any more Jewish than a spoon or a tree – which begged other questions. What makes me Jewish? What makes any of us who we are, or who we claim to be? Who are we really?

Identity and Empathy

These are our subjects today. One of Judaism’s jobs is to shape our identity – to teach us who we are and who we’re called to be, to imbue a sense of belonging and cohesion. And on Rosh Hashanah, the start of our year and ritual start of creation and peoplehood, it’s worth reaffirming those first principles.

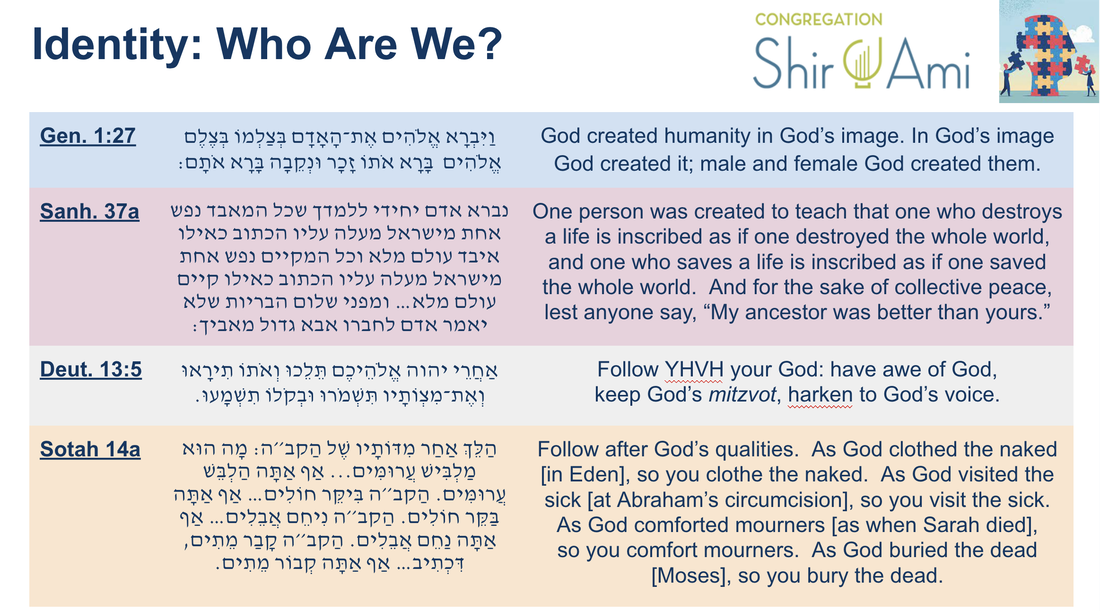

Judaism calls us all b’tzelem Elohim, in the divine image (Gen. 1:27). We each carry a sacred spark; we’re chips off the old block; creation’s light shines equally on us all. Therefore, the rabbis taught (Sanhedrin 37a) that each of us is a microcosm of the world, which we can save or destroy. We also are called to follow God (Deut. 13:5), but how can we follow what we can’t see? “Follow God’s qualities: As God clothed the naked [in Eden], so you clothe the naked. As God visited the sick [at Abraham’s bris], so you visit the sick. As God comforted mourners [when Sarah died], so you comfort mourners. As God buried the dead [Moses], so you bury the dead” (Sotah 14a).

From the start, Judaism encodes human identity to be inherently sacred and radically lowercase-D democratic. Next Judaism calls us to emulate God by a radically kind and giving way of life. Our core identity is both existential – factory installed – and also a call to action.

Onto these principles, Jewish self-concept layers our shared narrative that we renew today. We are spiritual descendants of Torah’s patriarch Abraham and Isaac, which is why today’s Torah reading was about them. Without Isaac, we’d have no ancestry.

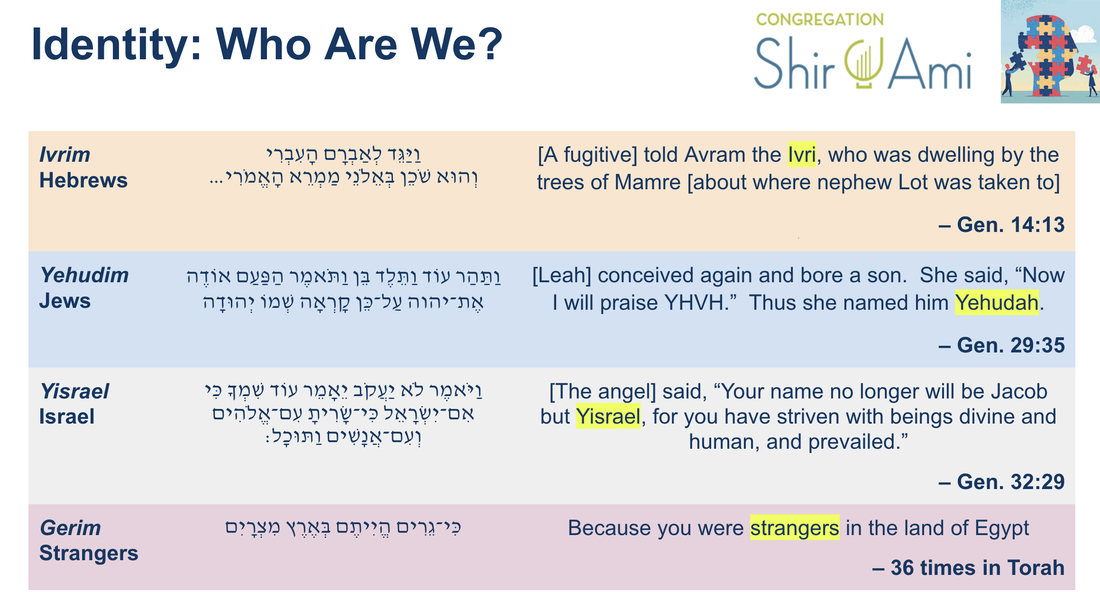

Through them, our ancestral monikers – Hebrew, Jew, Israel – encode deep meaning about who we’re called to be. Abraham’s neighbors called him “the Ivri” (Gen. 14:13) – one passing through, a boundary crosser. We Ivrim, Hebrews, are to be a people on the move, transcending limits real or perceived on our way forward.

The name “Jew” hails from Jacob and Leah’s youngest son, whom Leah named Yehudah, saying that she “would praise (odeh) God” (Gen. 29:35). We Yehudim, Jews, are called to be a people that praises in gratitude for our blessings and to keep renewing life.

“Israel” hails from Jacob’s famous dream of wrestling, in which he wouldn’t let an angel go without a blessing. The angel responded by renaming him Yisrael – striving with God (Gen. 32:29). We Bnei Yisrael, Children of Israel, are literally named Godwrestlers.

That’s our call of identity – to seek the Godspark in everyone, for we’re all b’tzelem Elohim; act kindly as a benevolent God might; transcend limits as Ivrim; praise in gratitude as Yehudim; and wrestle God as Yisrael in search of connection, blessing and transformation.

And one thing more: we’re spiritual descendants of slaves freed by a mighty hand and outstretched arm, in covenantal relationship with the Power of Liberation. Whether factual or mythic, it calls us to empathy. Torah repeats fully 36 times that our slave ancestors were strangers, so we know the stranger’s heart, and thus we must love the stranger as ourselves. We know what it’s like to be “othered,” so nobody is to be “othered” on our watch.

Onto these principles, Jewish self-concept layers our shared narrative that we renew today. We are spiritual descendants of Torah’s patriarch Abraham and Isaac, which is why today’s Torah reading was about them. Without Isaac, we’d have no ancestry.

Through them, our ancestral monikers – Hebrew, Jew, Israel – encode deep meaning about who we’re called to be. Abraham’s neighbors called him “the Ivri” (Gen. 14:13) – one passing through, a boundary crosser. We Ivrim, Hebrews, are to be a people on the move, transcending limits real or perceived on our way forward.

The name “Jew” hails from Jacob and Leah’s youngest son, whom Leah named Yehudah, saying that she “would praise (odeh) God” (Gen. 29:35). We Yehudim, Jews, are called to be a people that praises in gratitude for our blessings and to keep renewing life.

“Israel” hails from Jacob’s famous dream of wrestling, in which he wouldn’t let an angel go without a blessing. The angel responded by renaming him Yisrael – striving with God (Gen. 32:29). We Bnei Yisrael, Children of Israel, are literally named Godwrestlers.

That’s our call of identity – to seek the Godspark in everyone, for we’re all b’tzelem Elohim; act kindly as a benevolent God might; transcend limits as Ivrim; praise in gratitude as Yehudim; and wrestle God as Yisrael in search of connection, blessing and transformation.

And one thing more: we’re spiritual descendants of slaves freed by a mighty hand and outstretched arm, in covenantal relationship with the Power of Liberation. Whether factual or mythic, it calls us to empathy. Torah repeats fully 36 times that our slave ancestors were strangers, so we know the stranger’s heart, and thus we must love the stranger as ourselves. We know what it’s like to be “othered,” so nobody is to be “othered” on our watch.

Dozens of mitzvot for social justice cite this core empathy as their justification and our mandate. This is what we're called to do and be.

When Empathy Fails: Othering and the Return Call

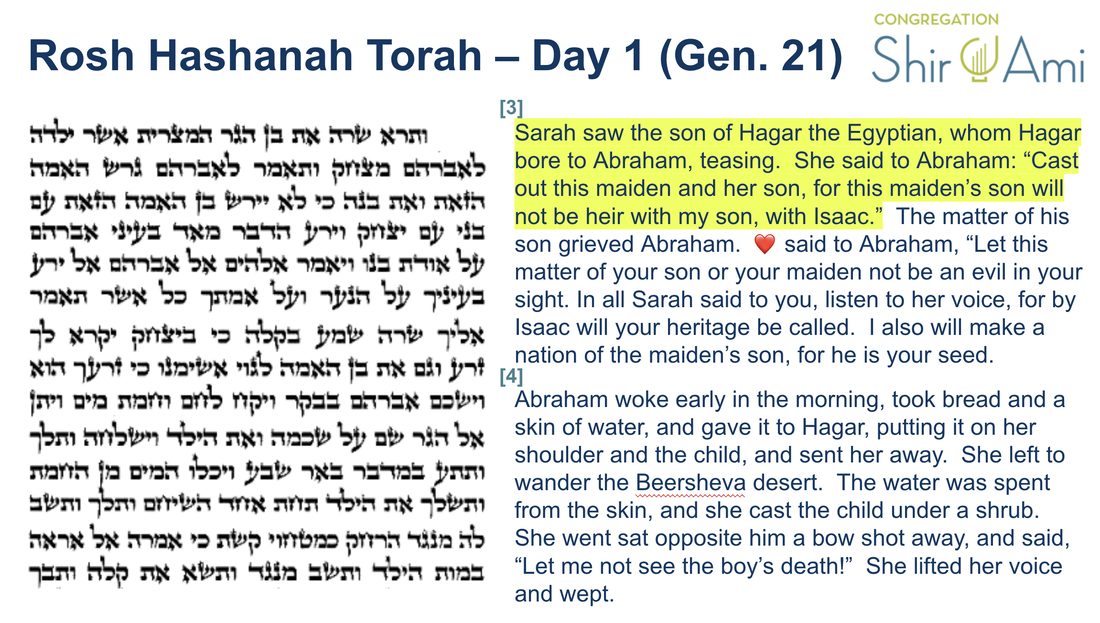

Now, what happens when our callings of Jewish identity and empathy – equality, kindness, praise, gratitude, Godwrestling, loving strangers – seem absent? Earlier today we saw one difficult example – in our Torah portion about our people’s origin story. Sarah demanded exile for Yishmael and Hagar, mother of the boy Sarah had called her own son. Sarah didn’t even say their names: they became “this maiden and her son.” So much for equality, kindness, gratitude, Godwrestling and loving the stranger. Instead, Sarah “othered” the stranger. Hagar’s name even means “the stranger.” Torah is yelling at us.

When Empathy Fails: Othering and the Return Call

Now, what happens when our callings of Jewish identity and empathy – equality, kindness, praise, gratitude, Godwrestling, loving strangers – seem absent? Earlier today we saw one difficult example – in our Torah portion about our people’s origin story. Sarah demanded exile for Yishmael and Hagar, mother of the boy Sarah had called her own son. Sarah didn’t even say their names: they became “this maiden and her son.” So much for equality, kindness, gratitude, Godwrestling and loving the stranger. Instead, Sarah “othered” the stranger. Hagar’s name even means “the stranger.” Torah is yelling at us.

Thankfully we needn’t venerate Biblical characters: Torah speaks through human humans –fallible, accessible, morally complex like us, like life. Had Hagar and Ishmael not been exiled, Isaac couldn’t be the ancestor of a nation: Israelites and Jews wouldn’t exist. But Sarah was unquestionably cruel. Jealousy and fear caused Sarah to “other” people once close to her – as jealousy and fear often can do.

We see it today. Modern politics are not only tribal and divisive but also hateful. Never in the history of polling has political dispute so widely leveled character attributions of stupidity, laziness, venality and corruption. Folks aren’t just wrong: they’re bad – devalued, “othered.”

Each of us has pulled a Sarah in one form or another. Maybe we didn’t exile anyone, but we labeled and “othered” them. We jumped to conclusions. We attributed motive. We let our jealousy, insecurity or hurt (however justifiable) eclipse our empathy and warp us. We saw people as their worst caricatures . Someone acts rudely or strange, and suddenly they are rude or strange. Someone lies; now they’re a liar. And once we label someone, once we “other” them, it’s difficult to back out of that box. Teshuvah becomes even harder.

Our nation's “othering” epidemic has become so widespread that none other than actor Matthew McConaughey just published a children’s book entitled “Just Because” that directly takes on the complexity of identity and behavior modification. “Just because I lied,” he wrote of his childhood self, “didn’t make me a liar…. Have you ever had your feelings hurt but forgiven someone anyway? Have you ever thought there was more than one right answer to a question? That’s because contradictions are all around us. And they make us who we are.”

We all wrestle, and the primordial light shines. We aren’t our worst mistakes – and if we’re not, then neither is most anyone else. Can we learn to see others and ourselves with this essential nuance?

It’s not easy. Our human complexity accretes instincts, snap judgments and patterns of behavior that escape our notice, until they don’t. But this season is about shining that primordial light on parts of ourselves that might lurk in shadows, and bringing compassion and discernment to them. This vision, too, is part of Jewish identity.

On the Front Line of Empathy's Battle with Identity

Last year, I was honored to participate in a multi-faith and multi-ethnic trip to Israel with the Jewish Community Relations Council. With me were clergy and lay leaders, folks of all colors and creeds, and elected officials. Our purpose was to build bridges among Jews and other community leaders, in the wake of massive spikes in antisemitism.

We see it today. Modern politics are not only tribal and divisive but also hateful. Never in the history of polling has political dispute so widely leveled character attributions of stupidity, laziness, venality and corruption. Folks aren’t just wrong: they’re bad – devalued, “othered.”

Each of us has pulled a Sarah in one form or another. Maybe we didn’t exile anyone, but we labeled and “othered” them. We jumped to conclusions. We attributed motive. We let our jealousy, insecurity or hurt (however justifiable) eclipse our empathy and warp us. We saw people as their worst caricatures . Someone acts rudely or strange, and suddenly they are rude or strange. Someone lies; now they’re a liar. And once we label someone, once we “other” them, it’s difficult to back out of that box. Teshuvah becomes even harder.

Our nation's “othering” epidemic has become so widespread that none other than actor Matthew McConaughey just published a children’s book entitled “Just Because” that directly takes on the complexity of identity and behavior modification. “Just because I lied,” he wrote of his childhood self, “didn’t make me a liar…. Have you ever had your feelings hurt but forgiven someone anyway? Have you ever thought there was more than one right answer to a question? That’s because contradictions are all around us. And they make us who we are.”

We all wrestle, and the primordial light shines. We aren’t our worst mistakes – and if we’re not, then neither is most anyone else. Can we learn to see others and ourselves with this essential nuance?

It’s not easy. Our human complexity accretes instincts, snap judgments and patterns of behavior that escape our notice, until they don’t. But this season is about shining that primordial light on parts of ourselves that might lurk in shadows, and bringing compassion and discernment to them. This vision, too, is part of Jewish identity.

On the Front Line of Empathy's Battle with Identity

Last year, I was honored to participate in a multi-faith and multi-ethnic trip to Israel with the Jewish Community Relations Council. With me were clergy and lay leaders, folks of all colors and creeds, and elected officials. Our purpose was to build bridges among Jews and other community leaders, in the wake of massive spikes in antisemitism.

In four whirlwind days, we were at the major religious sites, a Gaza checkpoint for an Iron Dome security briefing in sight of Hamas guns, in beautiful mixed Jewish-Arab cities for coexistence nonprofit leadership talks, meetings with Israeli Foreign Ministry representatives, at the Lebanese and Syrian borders, and – for my first time ever – in Ramallah to speak with leaders of the Palestinian Authority.

Entering Ramallah was entering another world. Just 10 miles from Jerusalem, it might as well have been a million. Checkpoints, barriers, barbed wire, the works. Our destination was the Palestine Football Association, which served the double purpose of offering somewhat more neutral territory for complicated face-to-face talks.

Entering Ramallah was entering another world. Just 10 miles from Jerusalem, it might as well have been a million. Checkpoints, barriers, barbed wire, the works. Our destination was the Palestine Football Association, which served the double purpose of offering somewhat more neutral territory for complicated face-to-face talks.

What we heard was hard to hear – some posturing and canned propaganda, some straightforward realpolitik. There had been plenty of posturing from the Israeli Foreign Ministry, too. Yet ultimately both expressed empathy for the other’s humanity and dignity, and said that their own identity was forever shaped and linked by wrestling together: Godwrestlers both – descendants of Isaac and Jacob, descendants of Ishmael. Nobody simplified the crushingly complex politics, or parried false relativism. There was, however dim, a light of shared humanity.

I exited the building into a world I hadn’t had time to notice going in. I was surrounded by Arabic: I was illiterate. Tight security was all around. Burning garbage stenched the air. Nationalist flags and signs were everywhere. My heart lurched with deep-seated caricatures that I’d unwittingly absorbed over time. I was safe but afraid, surrounded by otherness, so I myself felt othered. I wasn’t proud of it at all.

I exited the building into a world I hadn’t had time to notice going in. I was surrounded by Arabic: I was illiterate. Tight security was all around. Burning garbage stenched the air. Nationalist flags and signs were everywhere. My heart lurched with deep-seated caricatures that I’d unwittingly absorbed over time. I was safe but afraid, surrounded by otherness, so I myself felt othered. I wasn’t proud of it at all.

It was a "Come to Moses" moment for me in another way: I dedicate my secular life to a North Star principle of equal justice for all, in which everyone – regardless of who they are, or how they look, or whom they love – both gets and appears to get a fair shake. We who serve in the Judiciary must personify these principles of fairness and neutrality lest public confidence in the courts falter. Yet we all are prone to have implicit biases because we're people. So part of my equal-justice North Star is to actively search out even the slightest possibility of implicit bias in myself – anything, however remote, that might ever impel me to tip for or against someone because of who they are.

Standing in Ramallah, I felt that possibility for the first time in my life. Like Torah yelling through Sarah, Ramallah's impulse yelled through me. Immediately I knew two things: I need to speak it, and I had to redress it – for the calling of my Judiciary role, and for the calling of my own heart and spirit.

Fear tends to shrink us and lock us in; spiritually speaking, often the antidote is to reach outward toward our object of fear. So right then and there, I vowed to learn Arabic, to de-stigmatize some of the caricatures, build empathy, build relationships and pull out any implicit bias I could find – root and branch.

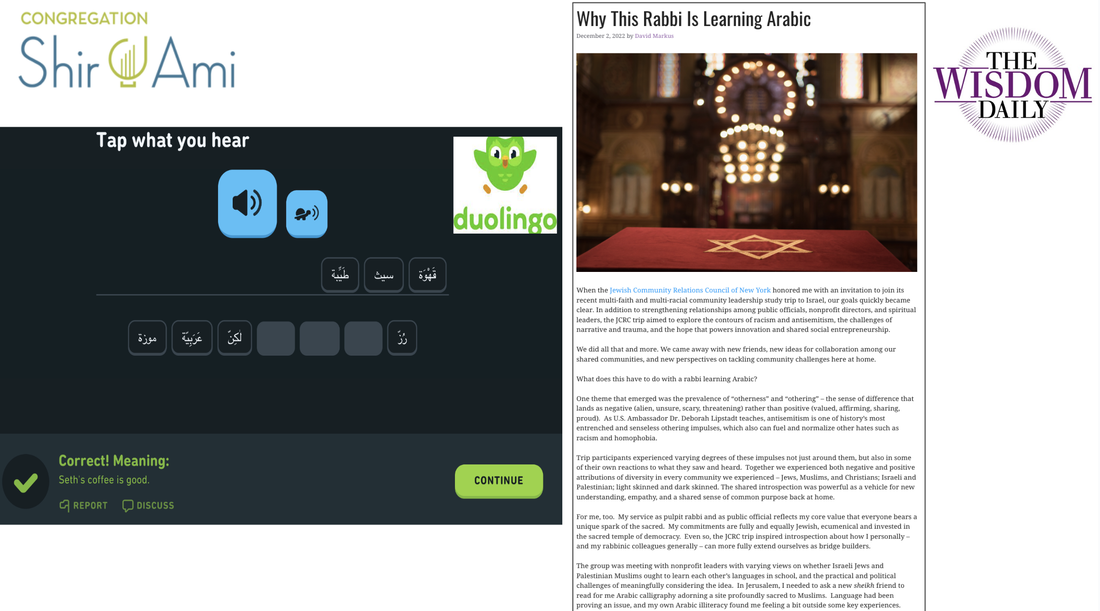

Thus began my foray into Duolingo, a language learning platform. It’s not an ideal way to learn, but it’s a start. Soon I could proudly say things like, “Seth’s coffee is good” (قهوة سيث جيدة / qahuwah Seth jéyidah) – not exactly a basis for peace talks, but slowly there was more peace within me.

My next time in Israel, four months ago on a congregational trip, was a bit of a healing. In Jerusalem and especially the Old City’s Arab Quarter, Arabic immersion didn’t trigger me. I could greet folks in halting, almost baby Arabic, enough to elicit genuine smiles and hugs.

An especially big hug came from Doris Hiffawi, whose home we visited for Arab hospitality and deep discussion of identity. Her Ajawi neighborhood in Jaffa is now part of Tel Aviv, but is clearly Arab. Doris told us how most Jews instinctively see her as Muslim, but Doris is Christian, so most Arabs also see her as “other.” Doris is a minority within a minority, a Christian among Arabs among Jews – and, she told us, seemingly nobody understands what it’s like to be her.

Standing in Ramallah, I felt that possibility for the first time in my life. Like Torah yelling through Sarah, Ramallah's impulse yelled through me. Immediately I knew two things: I need to speak it, and I had to redress it – for the calling of my Judiciary role, and for the calling of my own heart and spirit.

Fear tends to shrink us and lock us in; spiritually speaking, often the antidote is to reach outward toward our object of fear. So right then and there, I vowed to learn Arabic, to de-stigmatize some of the caricatures, build empathy, build relationships and pull out any implicit bias I could find – root and branch.

Thus began my foray into Duolingo, a language learning platform. It’s not an ideal way to learn, but it’s a start. Soon I could proudly say things like, “Seth’s coffee is good” (قهوة سيث جيدة / qahuwah Seth jéyidah) – not exactly a basis for peace talks, but slowly there was more peace within me.

My next time in Israel, four months ago on a congregational trip, was a bit of a healing. In Jerusalem and especially the Old City’s Arab Quarter, Arabic immersion didn’t trigger me. I could greet folks in halting, almost baby Arabic, enough to elicit genuine smiles and hugs.

An especially big hug came from Doris Hiffawi, whose home we visited for Arab hospitality and deep discussion of identity. Her Ajawi neighborhood in Jaffa is now part of Tel Aviv, but is clearly Arab. Doris told us how most Jews instinctively see her as Muslim, but Doris is Christian, so most Arabs also see her as “other.” Doris is a minority within a minority, a Christian among Arabs among Jews – and, she told us, seemingly nobody understands what it’s like to be her.

Israel is a uniquely meaningful place, partly because it reflects core truths about most everyone everywhere. The Holy Land is holy, but so is this place, even if holiness feels hidden. Israeli identity is extraordinarily complex and full of contradictions, but then again, so are our own identities. It’s difficult in Israel to escape the seemingly all-encompassing trap of seeing others as their worst caricatures, but how different is it here, really? Israel is just particularly loud and blatant about it, because so too are the circumstances.

Doris’ family has been brewing coffee forever, in ancient Mideast ways. I knew how to say coffee, and how to say thank you. I quickly looked up how to say “hospitality” and eked out one Arabic sentence: شكرًا لك على قهوتك وكرم ضيافتك، دوريس / Shukran lak 3la qahwatik wa-karam dhiyaafatik, Duris: “Doris, thank you for your coffee and hospitality.” I got one of the biggest hugs, and a few tears – just from one sentence.

Imagine what our world would be if we extended ourselves just a bit more beyond what most frightens or upsets us. Imagine what our world would be if we each stretched just a bit more into the equality, kindness, gratitude, Godwrestling and stranger love that are the core callings of our ancestral identity. It starts with us. It starts today.

We can choose to let our suffering, jealousy and fear harden us. Or we can let them soften us, and remind us that we know the Other’s heart because we’ve been the Other, too. Empathy is healing for most every felt sense of Otherness – most especially for our own.

Let this be the year we fully live our creed. It is on us, and within us, to do.

Let it begin with us, starting now. Shanah tovah.

Doris’ family has been brewing coffee forever, in ancient Mideast ways. I knew how to say coffee, and how to say thank you. I quickly looked up how to say “hospitality” and eked out one Arabic sentence: شكرًا لك على قهوتك وكرم ضيافتك، دوريس / Shukran lak 3la qahwatik wa-karam dhiyaafatik, Duris: “Doris, thank you for your coffee and hospitality.” I got one of the biggest hugs, and a few tears – just from one sentence.

Imagine what our world would be if we extended ourselves just a bit more beyond what most frightens or upsets us. Imagine what our world would be if we each stretched just a bit more into the equality, kindness, gratitude, Godwrestling and stranger love that are the core callings of our ancestral identity. It starts with us. It starts today.

We can choose to let our suffering, jealousy and fear harden us. Or we can let them soften us, and remind us that we know the Other’s heart because we’ve been the Other, too. Empathy is healing for most every felt sense of Otherness – most especially for our own.

Let this be the year we fully live our creed. It is on us, and within us, to do.

Let it begin with us, starting now. Shanah tovah.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed